A Season in (Bureaucratic) Hell

Japan welcomes newcomers with a wall of administrative nonsense

Look, I realize you signed up for a Climate substack, not some dude’s travelog about moving to Japan. And yeah, I’ve been working on the climate stuff too —and will post on it soon. But just now, three weeks after landing in Tokyo, it’s hard to focus on much else. So yeah, this is a Tokyo post…and rather a whiny one, too, I’m afraid.

It’s hard to write about these three weeks without sounding like a whiny little bitch. It hasn’t been easy, though nothing really serious has gone wrong. It’s just been…aggravating, in a drip-drip-drip sort of way where no single thing is a disaster, but every little thing is hard.

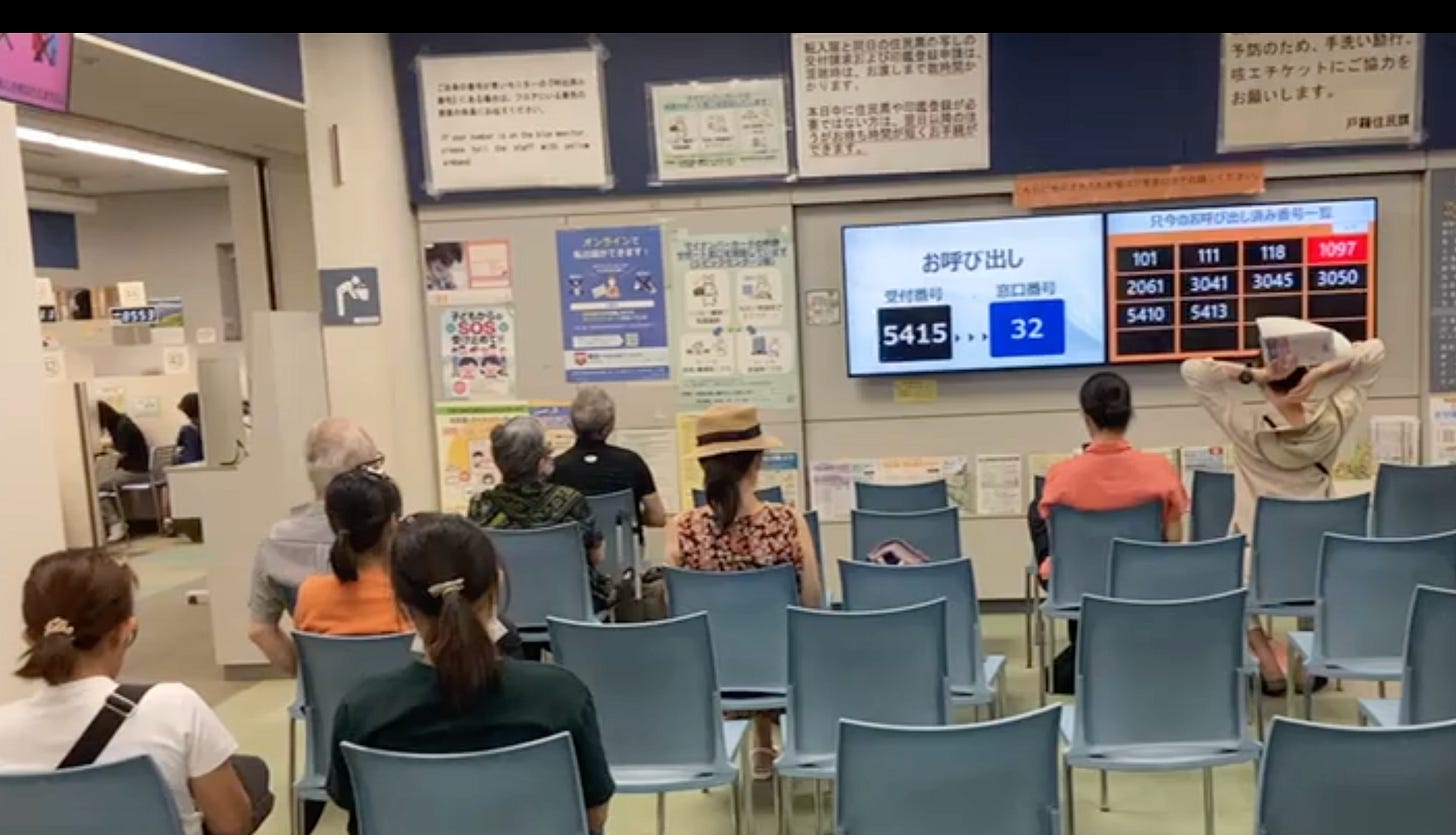

A lot of this is down to Japan’s particular bureaucratic culture. The stereotype is of a flawless bureaucratic machine, and that’s not exactly wrong. There’s a system for everything, and as long as you’re comfortably ensconced within that system, things work great.

Step half an inch outside the usual-way-things-are-done, though, and you discover the setup’s Achilles’ heel: utter rigidity.

Our first order of business was finding a place to live. A very nice agent took us around, we found a great place, and told her we’d like to apply for a lease.

“Sure,” she said, “just give me a Japanese phone number to put into the application.”

Erm, we don’t have one.

So off we go to the cell phone company to get a number.

“Uh, you’ll need to show us your municipal registration certificate,” they say.

I had no conceptual category for “municipal registration certificate.” But my wife explains, and the internet confirms, that whenever you move in Japan you need to go in person to register your new address in the municipal office.

So we trudge off to the government office and, guess what? We need a residential lease to register the address!

Ermm…this is Kafka territory now.

The reason, I think, is that nothing is set up for returning Japanese nationals. Live here your whole life and everything works great. Come as an expat and there are systems in place, procedures that are thought through for your use case. But come, as my wife is doing, as a Japanese person who hasn’t lived here for 20 years and there’s no system. Which means trivial things keep turning into baffling bureaucratic mini-quests.

Take the benighted new national ID system, the My Number Card. This didn’t exist back when my wife left Japan, so she never got one. Fast forward 20 years and you need a My Number Card to do pretty much anything. Try to explain that you don’t have one even though you’re Japanese because you’ve been abroad and you just get blank stares back.

Nobody’s thought through this eventuality.

You’re outside the system.

The fearsomely efficient administrative machine has no answers for you.

The bureaucrat in front of you will always be scrupulously, elaborately polite. They will bow and shower you in honorifics. They’ll leave you absolutely certain that they want to help you. But will they help you?

Nope. Not a chance.

So, look Amir, it’s been a slog.

We did finally get registered at the ward where our crappy temporary apartment is, just so we could get the certificate we needed to get the phone number we needed to apply for the apartment where we actually want to live. Only that one’s in a different ward, which means in a couple of weeks we’ll need to deregister here and re-register there, and only then will we be able to sign the kids up to school.

It’s the Nth ridiculous, tedious, soul-sapping work-around we’ve been forced into, but then swimming against the bureaucratic current is always a losing proposition in Japan.

I think it’s fair to say I’m pretty grumpy about the whole thing.

The kids, for their part, are coping by making a joke of the whole maddening situation.

“Pass me the salt,” our boy, who’s 10, will say at the breakfast table.

His sister, 12, goes, “sure, but could I just see your Salt Reception Registration first?”

“Sure, ” he shoots back, “I have my salt reception registration number, will that work?”

“No, I’m afraid we need to see your salt reception registration number card,” she says, adding “but don’t worry, to get the card all you have to do is show us proof you own salt.”

Then they both fall over laughing. And, all things considered, that’s probably the better approach.

Because the alternative is to just give in to the cumulative weight of aggravations: the oppressive summer heat, the miniscule, damp temporary apartment with its wheezing, asthmatic air conditioner and flaky internet connection, the random Buddhist holiday that shut everything down at the least convenient moment, the much-hyped Typhoon that shut everything down at the second least convenient moment and then veered off into the Pacific at the last minute, and just the general pervasive culture shock .

Still, it feels churlish to complain.

Nothing big has gone wrong, just a million little things. We did eventually get approved for a gorgeous —though small— apartment right in the center of Tokyo and life will be much nicer once we get to move there in a couple of weeks. The kids are healthy and in good spirits.

Things will turn around. Of course they will.

Soon.

Not yet.

But soon.

It was hilarious, my friend! I'm sorry for what you went through, but I couldn't help laughing out loud at some parts. Now I can see the context behind all the quality procedures and Toyota systems, and I understand why they work so seamlessly in Japan but can be challenging to adapt elsewhere. I especially loved the conversation between your kids about the salt certificate—they're so creative and fun! Their perspective really added a unique twist to your story.

I can't wait to see you in a couple of years, completely transformed into a bureaucratic, process-oriented machine ! Just imagine—every move you make, perfectly aligned with procedure, all with polite bow , It's going to be quite the transformation! 😂😂😂😂

Here is my contribution to your integration process 😉:

Bowing( *ojigi* (お辞儀))is an essential part of Japanese etiquette, and understanding its nuances:

1. Eshaku (会釈): A slight bow of about 15 degrees, usually used in informal situations, like greeting a coworker or someone of equal status.

2. Keirei (敬礼): A more formal bow of about 30 degrees, often used when thanking someone, apologizing, or showing respect to a superior.

3. Saikeirei (最敬礼): The deepest bow, about 45 degrees or more, used in highly formal situations, such as expressing deep gratitude, a serious apology, or showing great respect to someone of significantly higher status.

In addition to the angle and depth, the duration of the bow also matters. A quick bow can seem insincere, while holding the bow longer indicates greater respect or seriousness

My intense sympathy. All I can say is that it will get better once you manage to get past the first few hurdles.

When we moved to Japan we managed to do it in stages and that included my wife staying for a decent while with her parents - a place that she still had a drivers license for. This made things immensely easier. as it gave her a step to start on. I just showed up on a visitor visa until she had herself sorted out then my company applied for me to have a work permit etc. Yes I had been working here before but officially I was still based elsewhere and critically I was paid elsewhere