A Steam Engine for the Ocean

What if carbon credits are just fundamentally the wrong way to fund carbon removal?

“Much of the existing carbon removal industry is set up to produce painstakingly verified credits of permanently stored carbon for a handful of tech companies. It's not scaling to gigatonnes. It's not making a meaningful dent in atmospheric carbon dioxide. What it does is optimize for corporate sustainability departments' ability to claim precise offsets with minimal reputational risk.”

- Nick van Osdol and Paul Gambill

Our institutional infrastructure for carbon dioxide removal (CDR) is deeply broken, and this cracker of a post gets at the crux of it. Everybody should read it.

The short version is that the Voluntary Carbon Market is not a market at all: it’s a buyers’ cartel dominated by three players whose priorities are deeply distorting the way CDR is developing as a field.

Everybody in the CDR world is chasing after the smallish pot of money this carbon credit monopsony is dangling, which gives them hugely outsized power. And the direction they’re giving the nascent sector is highly unlikely to get us to gigaton-scale CDR anytime soon. (But don’t settle for my quick gloss, you really ought to read their thing.)

I’ve been fretting over these same problems, but I’ve landed somewhere very different.

Are we really sure carbon credits are the best way to finance gigaton-scale carbon dioxide removal? I no longer think so.

To explain why, I need to share a little fable with you.

London, Winter of 1712

It’s wet. And cold. The little ice age is on. It’s miserable.

Everybody hates it.

A gaggle of visionary scientists decides they’ve had enough. They gather to do something about it.

They’ve worked out that they could raise mean global temperatures by adding carbon dioxide to the atmosphere. Now they just need to figure out a way to finance this plan.

One eminent scientist steps up to share his vision:

“Gentlemen, we know the best way to warm the planet is to add carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, and the best way to do that is to burn large amounts of biomass. I’ve calculated that burning down the Amazon rainforest would release enough CO2 to raise the global temperature by2 degrees, which should be enough to get us past these miserable London winters.”

Nods of agreement.

“The Amazon is the ideal place to do this: nobody lives there, and there’s enough biomass there to do the trick. We’ve raised enough awareness about the problems associated with cold that there are now several city merchants willing to finance this.”

Applause!

“So here’s the plan: we’ll calculate how much jungle we need to burn to produce one ton of carbon dioxide, and they’ll pay us a certain amount of money for one ‘carbon credit’ each time we show we’ve burned enough jungle to add a ton of carbon to the atmosphere. Later, they can take those credits and bank them, trade them, do whatever they want with them! See? It's a market-based solution!”

Everyone in the room agrees, except for one man. He raises to his feet, tentatively, and asks.

“Yes, quite. But just to be clear, these ‘carbon credits’, they’re not producing any benefit directly for the people buying them, are they?”

“Well, not directly no,” the scientist concedes, “ we’re asking them to buy them because to contribute to this great collective endeavour of fighting the cold!”

“Right,” the doubter goes on, “but in terms of pounds and shillings and pence, this is, from their point of view, a form of…charity, isn’t it?”

“Heavens!” the scientist protests, “a warmer environment is in everyone’s interest!”

“Well yes. Certainly! It’s just that, well, most people aren’t that committed to the good of humanity…none of our funders needs to burn the amazon, do they? To them, the carbon benefits will always be ‘nice to have’, never a ‘must have.’ Now, is that really going to be a stable basis for achieving our goal?”

“Well, how else do you propose we finance an enterprise on this scale? We’re talking about adding billions upon billions of tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere!”

“Well, exactly,” the doubter goes on, “we need to give people a compelling reason to do things that have the effect of heating the planet. I’m talking about things that benefit them, right here and now while also contributing to that larger goal.”

“I don’t have any idea,” the scientist scoffs, “what you could be driving at, Mr. Watt.”

“Please don’t misunderstand,” James Watt says, “I share your commitment to raising global temperatures. It’s just that a financing mechanism that’s always one business downturn from your donors walking away can’t be a reliable source of long term financing.”

Gasps from the audience.

Somebody from the back shouts “what’s this magic way you have to finance it then, James?!”

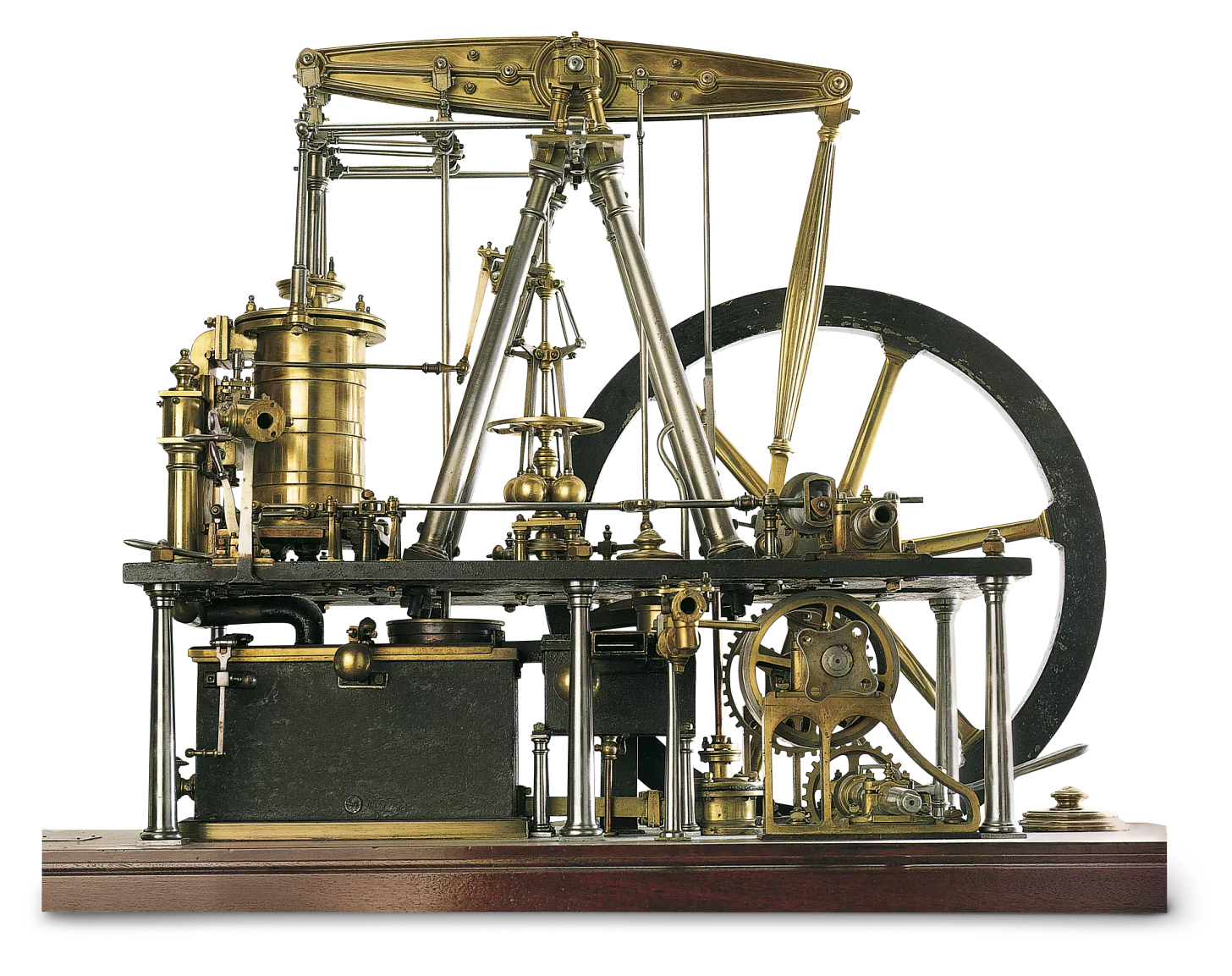

“I’ve brought this design for what I call a ‘steam engine,’ you see,” he says, rolling out the blueprints.

“It runs on coal, so it belches out great big puffs of carbon dioxide. Ideal for our ends, you see? It’s just that this engine…well, it doesn’t just emit carbon dioxide, it also does the work of four horses!”

“What could horses possibly have to do with the great task of raising the temperature?” the first scientist spits out, disgusted.

“Well, see, because people will gladly pay money for a machine that replaces four horses. They’ll line up to buy these, and not even for climate reasons. They may not even know that they’ll be heating the planet, and they’ll still want them.”

Murmurs rise from the crowd.

“The buyer need not even know this is heating the climate. We may be better off not talking about that aspect. Because raising the temperature isn’t really going to motivate that many buyers, beyond a few wealthy and public spirited backers willing to pay now for a benefit that may not be felt for decades, even centuries. But a machine that does the work of four horses now, that’s something you need now.”

“Hmmmm,” a bystander chimes in, “so on top of selling the carbon credits, which is what this is really about, you’d also have these co-benefits, like the thing with the horses?”

“No, you’re thinking too small,” Watt snaps back. “You need to flip the way you think about this altogether. Carbon credits are a dead end. The way you make certain carbon dioxide concentrations continue to rise for years, for decades, even centuries is to provide a service so amazing, so compelling, so world-changing that after a while society as a whole just doesn’t work without it! Energy! Energy is the benefit. We can’t live without energy! Heating the atmosphere is just a co-benefit, the cherry on top!”

A Steam Engine for Carbon Removal

Nothing like that happened in 1712, of course. But maybe the opposite needs to happen today. Focusing too much on voluntary carbon markets looks to me like a mistake, because they amount to a sophisticated 21st century version of philanthropy. And philanthropy will always be fickle.

As a financing mechanism, these markets are small and fragmented and they may never grow beyond this stage.

But find an activity that is compelling in its own right that also happens to draw down a significant amount of carbon dioxide on the side and the calculus changes.

This is the reason to think of ocean fertilization as Ocean Abundance Restoration.

Because when you fertilize ocean deserts and help increase ocean productivity and overall biomass, you produce benefits in a dozen different ways over and above the carbon drawdown.

Fisheries are a massive global industry: more than 3 billion people worldwide get at least 20% of their protein from the sea. Worldwide, 492 million people get some income from fishing, and 39 million are directly employed full-time in wild catch fishing. Fishmeal —protein-rich animal feed made from fish— is a $10 billion market.

More productive oceans means more fishing jobs, cheaper fish for people and animals feed. It means improved coastal livelihoods and food security for some of the world’s most vulnerable people. Ocean abundance means more whales for tourists to ogle at, more krill to feed those whales but also more krill for humans to turn into feed for livestock.

Ocean abundance is something people would benefit from even if it didn’t capture large amounts of carbon dioxide. Which is why Ocean Abundance Restoration is the kind of multi-decade effort we may be able to sustain even if climate change falls out of the headlines, even if the bottom falls out of the Voluntary Carbon Credit market, even if a troglodyte gets elected to the White House. Once we start doing Ocean Abundance Restoration, we are going to keep doing it because it is desirable in its own right.

In the Ocean Fertilization community, we’re typically shy about making too much of the ecological impact of this technique. This is in large part because the first guy who thought of this turned out to be a colossal charlatan who set the field back a dozen years. The Haida fiasco of 2012 certainly created a bit of a taboo around this framing But Haida having been a shit show in no way changes the simple reality that boosting fish and krill populations is an easily foreseeable side-effect of adding nutrients to oligotrophic waters.

I think it’s time to rescue this idea from the accident of its parenthood. Because fisheries worldwide are struggling. European fishermen are barely hanging on, as are many in Asia. Fish stock collapse is an issue in Chile, Canada, Japan, Namibia, Norway, India, all around the world, really.

People worldwide have a direct economic stake in sustaining ocean abundance. It’s just that the most promising technique we have to restore fisheries also happens to draw down carbon dioxide. Think how powerful a combination that is!

There will never be a direct political or economic constituency to support Direct Ocean Capture there way there is one to sustain ocean nutrient fertilization. Ocean alkalinity enhancement will never be at the heart of a coastal community’s livelihood strategy. These techniques will always be exposed to the vicissitudes of changing governments, morphing corporate commitments, even just political fads. They’ll never be really sustainable, because they’ll never be cash flow positive.

Ocean abundance can be a steam engine for ocean carbon dioxide removal: a service compelling enough to be unstoppable. It is the only technique I know of that you can imagine people uninterested in climate change fighting passionately for.

That’s power: the kind of power it’ll take to draw down carbon dioxide by the tens of billions of tons a year.

This is interesting, and a clever allegory. But I'm confused by a few things. I have an open mind about ocean fertilization (OF) as a safe way of stimulating growth of phytoplankton. But there are so many other things going on in the ocean as well.

First, by now some of the changes in fisheries are matters of ocean physics: because of ocean heating, certain currents and the points where they turnover and upwell nutrients are moving poleward, such as off Japan's coast. What is the time frame in which OF will reverse these trends -- assuming it will at all? Because if the timeframe is too long, then many countries might not see their coastal fisheries recover at all, despite OF.

Similarly, you've mentioned in other posts that OF will improve the Earth's albedo: but how much of the ice caps at the poles will have melted by the time OF starts to reverse ice cap loss, if ever? How much will ocean circulation have changed by that time because of the fresh water introduced into the system, and how much will sea levels have risen, potentially ruining the coastal communities you say OF will save?

Second, the notion of using ocean fertilization to grow feed for livestock doesn't sound like a winner. Shouldn't we concurrently be reducing dependence on livestock -- on grounds of CH4 emissions, deforestation, human health, biodiversity loss, etc.?

Third, there isn't anything in here about "ocean abundance" for the sake of non-humans. E.g., whales aren't just for tourists to ogle at: they were living in the ocean long before we started exploiting it, and are part of important food chains from the surface to the deep oceans.

If one takes the position that extreme anthropocentrism like in this piece is the only "realistic" philosophy, you'll have a self-fulfilling prophecy; and all non-humans will be in essence either farm animals or zoo animals (food or entertainment). Is that the kind of planet people want to live on?

More generally, what evidence (published, peer-reviewed) is there that OF will have all these knock-on benefits, and no drawbacks?