Here comes the propaganda

Bill McKibben, America's most influential climate activist, has written a very silly book

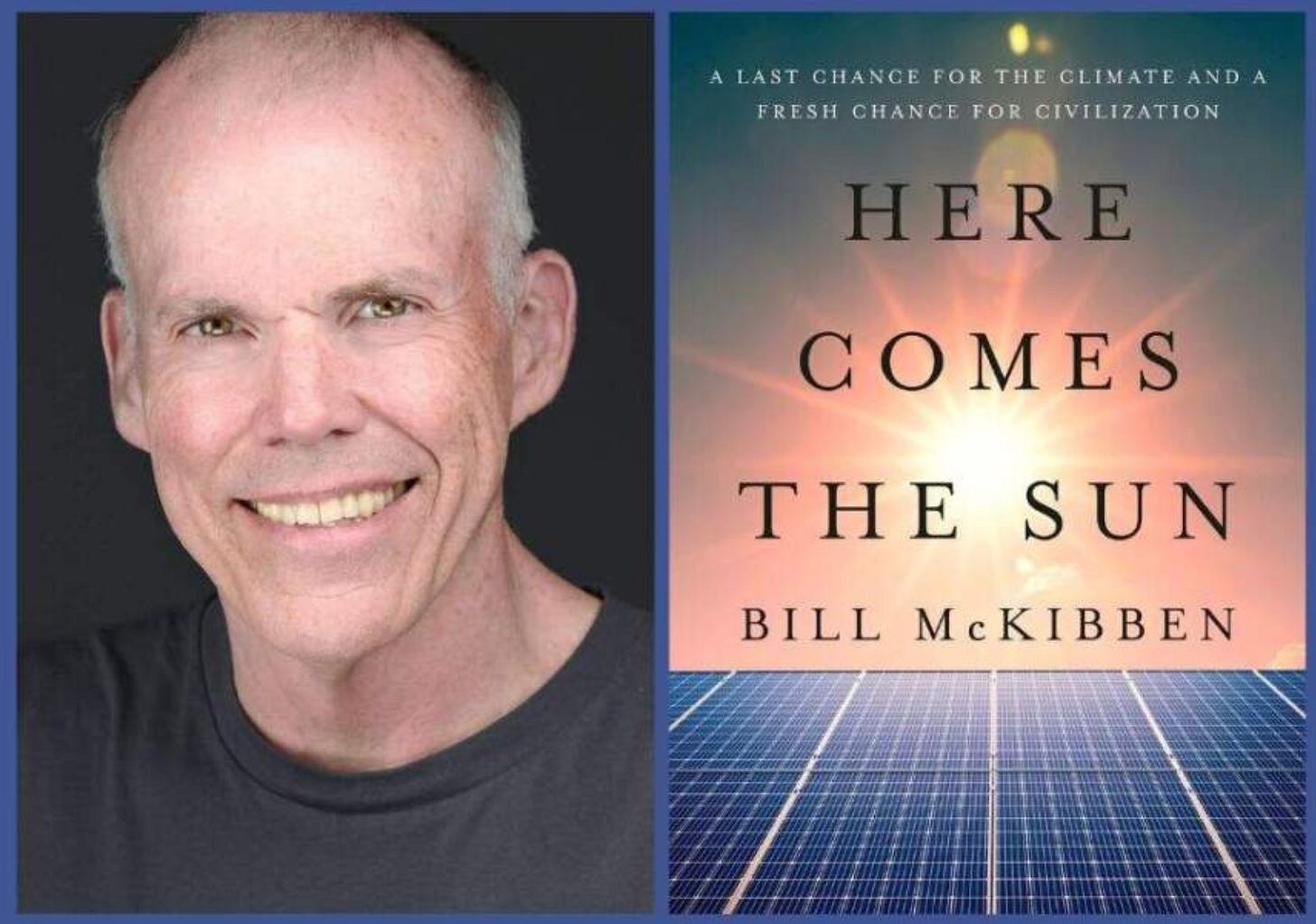

Solar energy emits no pollution and generates electricity pretty much for free when the sun is out. That, right there, is the TL;DR to Bill McKibben’s breathless panegyric Here Comes the Sun: a book that belabors two points to death while studiously avoiding anything like a realistic appraisal of solar energy’s potential.

McKibben, often described as America’s most influential climate activist, is determined not to complicate things. Over a slim 224 pages, you get lots of elaboration, lots of examples and vignettes and exhortations, alongside studied silence on the issues that make solar complicated: issues serious energy analysts have spent considerable energy studying, but Bill McKibben has nothing to say about.

Surely he knows better. Bill McKibben knows —everyone knows— that the sun doesn’t always shine. He must realize intermittency has major implications for solar adoption. He ought to know that the things you have to do to shield power grids from the vagaries of intermittency can more than double the cost of providing zero-carbon electricity, enough to nullify the cost advantage solar has when the sun is shining. He must know that, for this reason, real world grid operators usually backstop solar generation by keeping old coal or gas-fired power plants running as backup. He ought to realize that this leaves solar joined at the hip with its supposed ideological rival: fossil fuels.

Bill McKibben must know all of this. He’s spent decades on this beat, he can’t not know it. But you can read his tendentious little pamphlet from start to finish and never guess that any of this is an issue. Because he’s not trying to inform you, he’s trying to evangelize you. So he keeps his narrative simple, clean, straightforward and utterly misleading.

I’d known Here Comes the Sun was out for some time, but only read it from start to finish after I had lunch with an old, dear friend in Washington last month. Sent home without pay for the length of the government shutdown, Sarah (not her real name) was whiling away the hours at home and exploring new career options.

“I’ll probably try to get a job for a non-profit installing solar in the developing world,” she told me. “I just read Bill McKibben’s new book and…”

That was a jolt. Sarah is one of the smartest people I know — a superstar analyst with the kind of intellect you gawk at in awe. That people like Sarah are making career choices on the basis of a book this threadbare strikes me as both a testament to McKibben’s skills as a propagandist and a kind of crisis for the climate movement.

“Shit,” I thought to myself, “I’m going to have to actually read it.”

My expectations were not high, but still Here Comes the Sun failed to rise up to them. I had expected the steelman version of the solar-max argument. Bill McKibben is so famous, so powerful, so influential. I imagined him wrestling with the problems actual energy experts spend their time grappling with, and putting forward a powerful argument on behalf of his preferred solution. I was a bit intimidated at the prospect of picking a fight with such a powerful figure on such a sensitive topic.

I had expected far too much.

Rather than fighting the good fight on behalf of solar, McKibben elides the whole discussion. Obvious rejoinders, the types of things anybody calling themselves an energy analyst cannot help but be aware of, simply go unaddressed. Instead, he lards on one anecdote on top of the next to make it seem like there’s no debate at all, that the only doubters are paid up stooges for the oil industry.

Take the whole benighted subject of subsidies. McKibben spends a lot of the book talking about “life on the steep part of the S curve” — just the startling speed of solar installations in recent years. Spend any time at all looking at it, and you realize very quickly that this is a story about Chinese government policy.

Back in 2010, China declared solar a strategic emerging industry. Since then, it has spent lavishly to corner the global market on solar pv manufacturing. The subsidies come in many forms: from feed-in-tariffs that amounted to a large cash giveaway to solar manufacturers to concessional credit, export assistance, tax breaks, land giveaways, the works. The result has been massive manufacturing overcapacity: lured by free government money, hundreds of Chinese firms rushed into the sector, resulting in a glut of solar cells. These end up selling for a fraction of what it actually cost to manufacture them. Then, on the American side, the Inflation Reduction Act piled on its own set of subsidies for installing the darn things. Of course solar generation’s now very cheap to consumers — consumers pay a small fraction of the cost of solar generation.

Bill McKibben knows —he couldn’t help but know— that the story of solar’s rapid adoption is as much an outcome of Chinese and American (and European, and Japanese, and, and…) subsidies as it is a story about improving solar technology. California alone subsidizes solar generation to the tune of $8 billion a year. McKibben must know that investors are sometimes impolitic enough to admit that the only reason they put money into solar is to grab those sweet, sweet IRA tax credits. This shit is so basic.

And yet you’ll flip through the book looking for a defense of solar subsidies in vain. Instead, McKibben tells the story of solar’s falling costs as simply a tale of technological progress. Pay no attention to the subsidies behind the curtain.

Again and again, Here Comes the Sun simply sticks its head in the sand rather than grappling honestly with the serious issues mass solar adoption raises.

And it’s not just subsidies. Take the issue of the non-linearities in the cost of firming. Solar power is notoriously flaky due to those twin energy crises: sunsets and clouds. “Firming” a power grid (that is, hardening it against the effects of intermittency) is not so hard when solar is a small part of your generation mix. But firming costs explode as solar penetration rises. The higher the proportion of a grid’s generation is solar, the more back-up power sources you need for when the sun flakes out. Intermittency forces grid operators to make difficult choices about what to do with all the excess generation at noon, which is not when people demand the most power, and how to make up the deficit in the evening, which is when they do.

All of this costs money, and those costs don’t rise in a straight line — the more solar you have, the more expensive it becomes to bring on a little bit more. To people who actually understand energy economics, this non-linearity is one of the biggest question marks hanging over solar: at what point do solar firming costs overwhelm the cost advantage it has when the sun is out? A lot depends on the specifics of your grid, but at somewhere between 15% and 50% of solar grid penetration, adding one more unit of solar power costs more than the unit can be sold for.

So where are you going to get the other 50-85% of you power, Bill?

Maybe he knows, but he sure as hell isn’t telling us. McKibben keeps noting that battery costs have come down sharply over the last three decades, but he’s careful not to say outright that grid-scale batteries are now affordable, because they’re definitely not. He’s deeply invested in portraying solar as a replacement for fossil fuels, which is why he steadfastly obfuscates the awful truth: that, in the real world, gas and coal are the only affordable firming options, which means solar complements fossil fuels much more often than it replaces them.

Or take price volatility — the swings between times when the sun is out and when it’s not. Volatility also seems to increase as solar penetration rises — what you’d expect, since higher penetration amplifies the boom-and-bust generation cycle. This matters, because the kinds of industrial firms that buy a lot of electricity —think aluminum smelters— often work on thin margins, and can’t really operate if they can’t predict how much power is going to cost from day to day, or even hour to hour. Which means manufacturing firms tend to curtail operations and redirect investment to lower-cost jurisdictions when power grids cross certain thresholds in solar adoption.

McKibben’s blindspots have obvious political implications. Ignore non-linearities and you set the stage for an almighty political backlash against the entire green energy project. That’s a backlash that has already begun, in Germany and Britain and the U.S., as voters appalled at rising power bills turn to the denialist right. It’s a backlash you might prepare for if you knew to be on guard for it. But readers of Here Comes the Sun won’t be on guard for it, because Bill McKibben refuses to talk about any of this.

That America’s most influential climate activist could write a book this threadbare, that it could influence smart, capable people like Sarah, paints a picture of the sorry state of intellectual involution the climate movement has reached. Rather than a serious discussion about the obvious benefits and very real limitations of this important technology, McKibben’s given us a load of unthinking propaganda, a pollyannaish screed so devoid of nuance it ends up leaving readers knowing less at the end of the book than they knew at the beginning.

I heard Bill McKibben speak last fall at a small public talk in Vermont.(I even sat next to him in the front row before he spoke). I first became acquainted with him about 25 years ago when I participated in a localvore challenge in Vermont. He was one of the founders of the eat local movement in Vermont. You have to give him credit for bringing the issue of how burning fossil fuels has changed nature and climate. But having identified the problem he has through his organizations and activism attempted to solve the problem. I have subscribed to his Crucial Years here on Substack for the past year and he definitely suffers from confirmational bias. He wears the white hat of saving the planet by adopting renewables while he identifies Trump and his fossil fuel friends as the enemies of "the fight". Sadly as you point out he doesn't seem to be able to go off script when discussing climate change. I have canceled my subscription to his comments. I wont bother to read his Here comes the Sun. I am reading your book.

It's wrong to say the only affordable sources of energy are Coal and Gas. How could we know that? Nuclear energy has the potential to be 1000 times cheaper. We won't know what today's price really is until someone builds a modern factory making nuclear modules, redesigned in 2025. But we do know the fuel is so cheap as to be threatening "too cheap to meter" to the capitalist industry. Manufactured reactors could be built at about the same price as heavy diesel, and with fuel that's 1000x cheaper, and far less pollution or waste. The fossil fuel industry cannot compete so they distract us, as you say, with chaotic energy sources that cement demand for Gas. Wind and solar are like the guy who spins the roulette wheel. California has a casino called CAISO where speculators gather every afternoon to bet on when clouds will quench wind and solar farms. Frackers sell wee bits of gas at fabulous prices when Solar takes the day off around 4:20 pm, saving us from the manufactured emergency. Nuclear energy ruins the party, providing power 95% of the time except for scheduled interruptions-- speculators can't bet against that! Nuclear energy cuts down costs for consumers but is bad for fossil generators and utilities.

Mckibben only mentions nuclear energy in passing as "a side dish", if costs ever come down. He claims nuclear energy is a distraction, ironically "in the distorted infosphere of green-wash and spin we inhabit". McKibben is in the anti-nuke cult, and it's hard quit your religion.

The cult of anti-nukism has roots in goodness and generosity, as well as racism and fossil fuel boosting. They recite a mantra of whataboutism. "whatabout-the-waste, cost, proliferation". Such arguments are easy to refute in reality, but that doesn't change anti-nuke beliefs that are "beyond" logic.

When I was a teenager the arms race was really scary. President Reagan was building expensive and destabilizing weapons that could only be used in a surprise sneak attack on USSR. If USSR attacked first the weapons would be useless. Was the USA planning a sneak attack as in Dr. Strangelove? Billions of dollars suggested "Yes". I was surprised that once the Peacekeeper missile was complete, the Pentagon mothballed it. They didn't need it. Just needed to be paid to build it. A Boondoggle. I'm more alert to govt programs that exist only for the contractors now.

Given the immediate existential threat of climate collapse via mutually assured destructive nuclear war, stopping the arms race was the most environmental thing to do. PR experts at Sierra Club and other places decided that people weren't smart enough to be able to tell nuclear energy from nuclear bombs, and went full-court-press against anything "nuclear-".

Supporters of Oil and Coal found it convenient to amplify the anti-nuke movement, using Peace and Environmental grounds, rather than expose their anti-competitive agenda. Groups like RMI then dedicated to the "more efficient" use of coal. And FOE "Friends of the Earth" was funded with an initial $200k from the Oil company Atlantic Richfield's head. See Engdahl's _Century_of_War:_Anglo-American Oil Politics and the New World Orders for more.

McKibben cannot explain where the solar panels and batteries come from. They are NOT made with solar energy! Today they are made with coal, as no one can run industry on solar power. His focus on the grid is silly. Most of our energy demand is for buildings, and minerals, and transportation, which today is 0% supplied by solar.