Our climate funding priorities are totally crazy and weird

Why the most effective, least expensive climate policies keep getting nickel-and-dimed

Fertilizing ocean life is the smartest, safest way to reverse climate change. The place to start is algae: the primary producers that sustain marine life. When healthy seaweed thrives, so does the whole ocean. A thriving ocean takes up far more carbon dioxide than a depleted one. Enough carbon dioxide, quite possibly, to stop climate change altogether.

Fertilizing ocean life, then, ought to be the core of a whole-of-humanity push to repair the climate.

And we barely fund it.

This is confusing. Governments are happy to spend eye-bleeding sums on measures that aim to slow climate change on the margin. Massachusetts is on the verge of spending $10 billion on a project to install enough batteries to keep its grid running on cloudy, windless days for a grand total of four hours. Germany is spending €14.4 billion to pay people to replace outdated heating systems with energy-efficient heat pumps. France is spending €5.8 billion to make old homes more energy efficient. China is spending $72 billion subsidizing new electric vehicles. (And those are the good investments — I’m not even talking about the huge oil-and-gas subsidies that directly underwrite actual emissions.)

Meanwhile, a world-class, all-bells-and-whistles ocean fertilization trial might cost $150 million — that’s with an “m”, not a “b”. And yet trials on that scale are impossible to finance. The groups I’ve talked to are fighting tooth-and-nail to fund trials in the $500,000 to $10 million range, and even then it’s a tough slog.

There’s no other sphere I can think of where the disconnect between cost and benefit is this wide.

Even if successful, billion-dollar abatement programs to tackle a given emissions source in a single jurisdiction won’t solve the problem. They don’t set out to solve the problem. They aim to slow the rate at which greenhouse gases build up in the atmosphere, not to stop that build-up. Much less to restore a safe climate.

Yet governments are happy to fund them, while they refuse to fund the kind of research that could very well end the climate crisis.

Spent wisely on a concerted push to boost marine photosynthesis, the $10 billion Massachusetts is devoting to batteries could stop climate change altogether. For everyone.

Somehow, people can’t see it.

It’s as though climate change, through its sheer scale and weirdness, renders us incapable of thinking logically about our options. We’re fine burning billions to reduce a single source of carbon dioxide in this or that country, even though that barely makes a dent in the overall problem. But we won’t spend a tenth of that to restore a safe climate.

How did we back ourselves into this corner? Why did we narrow the Overton Window on climate solutions so early?

At the start of the century, mainstream climate activists saw that greenhouse gas emissions were the source of the problem and jumped directly to an almost exclusive focus on emissions abatement. Nobody, it seems to me, really thought through the implications. Nobody foresaw how poisonous the politics of forcing higher energy costs on everyone would be. Nobody grasped the imperative for developing country leaders to make as much energy available as cheaply as possible. We just committed way too early.

By the time the drawbacks of this path had become impossible to miss, the climate movement was committed to non-solutions on an ideological level. As governments started to lose office, in part, over energy cost revolts, greens got tribal about it, increasingly confusing means with ends. They came to nurse an unthinking distrust of alternative approach. Some built a rejection of the most promising techniques into their political identity.

This might not be so bad if, as a strategy, emissions abatement worked.

But it doesn’t.

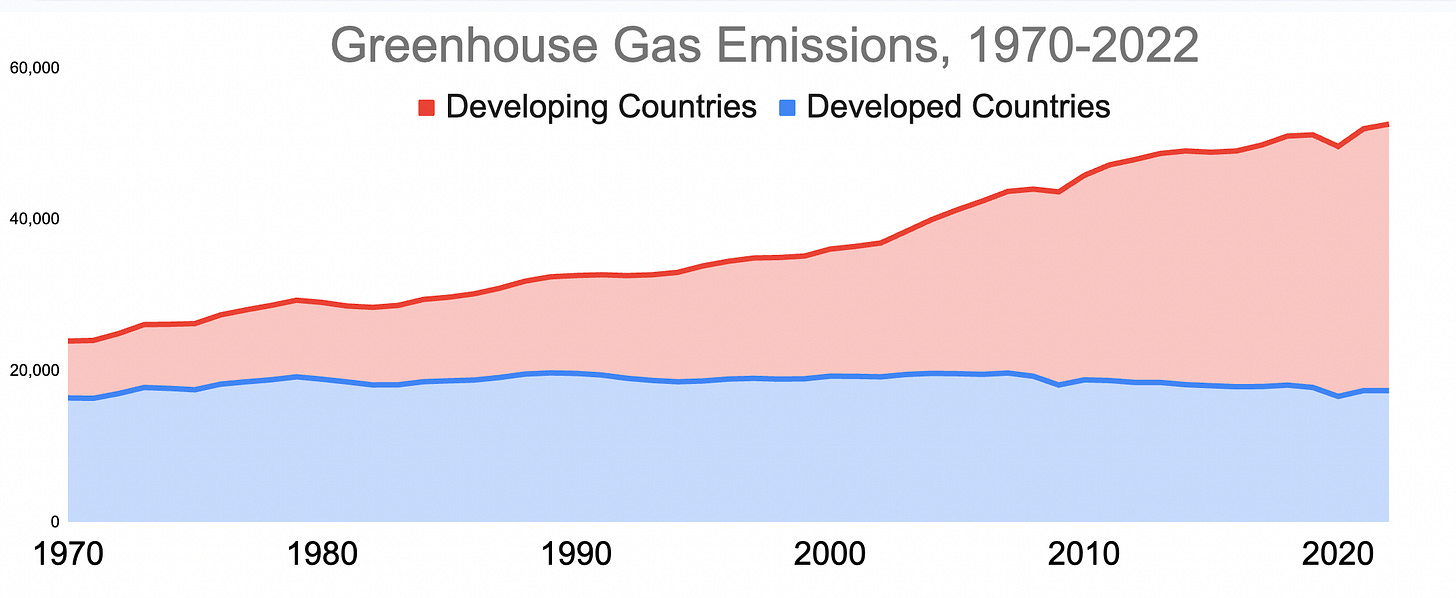

At ruinous political and economic costs, the climate movement bought itself a slow, gradual reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from the developed countries. Because annual rich country emissions did fall, a bit, from a high 19.7 billion tons of CO2 equivalent in 2007 to 17.4 billion in 2022.

That modest victory, however, was easily overwhelmed by the explosion in emissions from the Global South. For every one molecule of CO2 equivalent developed countries stopped emitting after 2007, developing countries added five. The developing world now accounts for 70% of emissions, and growing. The results of 30 years of UN climate conferences is that climate change is still accelerating.

It makes me angry that we’ve wasted so much time, billions of dollars, and the energies of a whole generation of climate activists on a dead end. Worse than a dead end: we’ve turned safeguarding the climate from what it should have been —a shared commitment— into an ideological hot potato, something that divides us instead of uniting us.

Putting all of our eggs in the emissions-reductions basket isn’t just a failing strategy: it’s a strategy that already failed.

There are too many people in too many places with too many reasons to want fossil fuel energy for us to stop them. Short of recolonizing two-thirds of the world, the West cannot dictate energy policy to the developing countries that now account for basically all emissions growth. As the United States makes painfully clear, the West can’t even sustain an emissions abatement strategy in its own sphere, let alone trying to impose it on everyone else.

Surely we can all agree now that this strategy will. not. work.

We need to be realistic about the time scales involved. We can wean our species off GHG-emitting energy sources. In time, we will. But that project is going to take a century, not a couple of decades. Abatement is simply too slow a path to avert climate disaster.

Unless we broaden the climate Overton Window, we’ll be loading huge, reckless climate risks onto our grandchildren’s shoulders. We risk rendering whole swathes of Africa and Asia uninhabitable. It really is a kind of slow-motion crime against humanity.

It is not acceptable. I don’t accept it.

It’s also not necessary.

We have, within our reach, techniques to keep the climate safe for generations to come. We have very good reason to believe that restoring ocean abundance by fertilizing healthy marine plant life can safely sequester the excess CO2 we’ve put into the atmosphere. The ocean already contains 41 times as much CO2 as the atmosphere does: fertilizing marine plant life until that number rises to 41.3 would be enough to draw down all the anthropogenic CO2 now in the atmosphere. We have excellent reasons to believe we can do this affordably, within a couple of decades, and restore depleted ocean ecosystems in the process.

We can do this. We have to do this. Failure would count as one of humanity’s worst self-inflicted wounds. Our grandchildren would not forgive us. And nor should they.

“Meanwhile, a world-class, all-bells-and-whistles ocean fertilization trial might cost $150 million — that’s with an ‘m’, not a ‘b’. And yet trials on that scale are impossible to finance.”

If you are correct about this, then you or “your groups” should easily be able to find a single leftist billionaire like a Tom Steyer willing to fund such a proof of concept.

That you and they can’t means it’s likely - not guaranteed, but likely - that you are not correct.

Yeah, the funding priorities are totally off. Still, I don't think that's the main reason why such projects aren't being persued. Just like with housing projects, it's all too easy to stop geo-engineering projects by pointing to potential marginal ecological downsides. Some people are allergic to the concept of trade-offs.