Milton: Termination Shock Now

Ocean ships stopped brightening marine clouds; monster storms followed.

Look through press coverage of what’s driving monster storms like Hurricane Milton, and you’ll see lots of handwringing about climate change. What you won’t see is any mention of the maritime shipping industry.

Which is odd. Because the sudden surge in big storms isn’t caused by global warming in some general sense, but by a rapid temperature spike in the North Atlantic. And researchers increasingly suspect that the proximate cause for that spike is all about pollution from maritime shipping. Or rather, its sudden absence.

Let’s back up.

For decades, ocean shipping relied on the cheapest, nastiest gunk an oil refinery could turn out. Fuel for container ships and ocean tankers had sulfur levels that just wouldn’t be allowed for use over land.

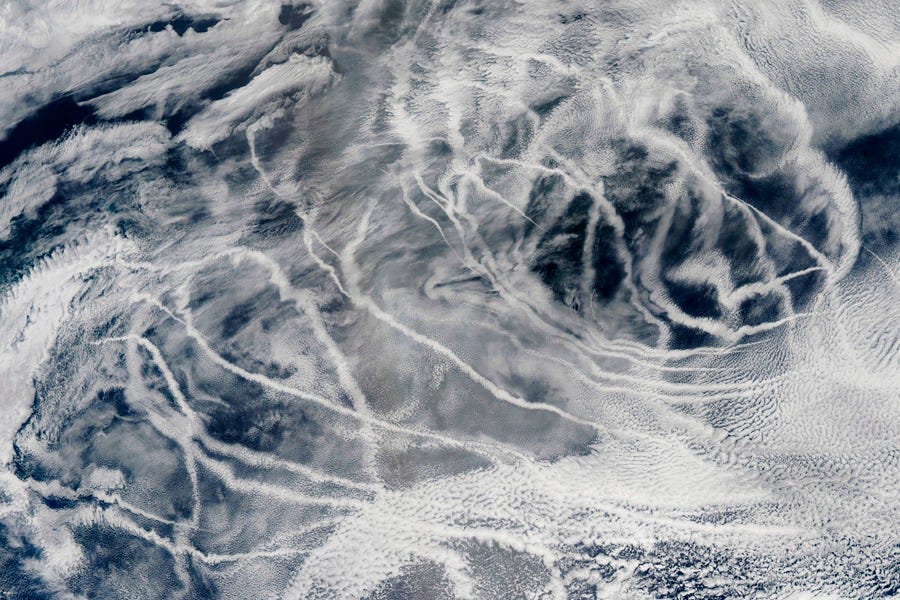

The sulfur compounds you get from burning this gunk turn out to be excellent cloud condensation nuclei: moisture condenses around these tiny aerosol particles, which is why ocean vessels tended to leave clouds in their wake. You could see them clearly on satellite images like the one at the top of this post, or just from the window of your jetliner over the Atlantic.

Researchers called them “ship tracks”. There’s a literature on them dating back to the 1990s.

The sulfur compounds that cause ship tracks are pretty nasty, though. They’re harmful to breathe, and they cause acid rain. Campaigners had been wanting to clean them up for a long time. Which is why, starting in 2010, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) introduced new, lower sulfur standards for ocean-going vessels.

At first, the rules weren’t very strict, and they didn’t make much difference to ship tracks. Then, in 2020, the sulfur cap was substantially tightened. And this did make a difference. A big difference.

Suddenly, from 2020, ship tracks largely disappeared. And this had consequences nobody had foreseen.

Right away, clouds over shipping lanes got less bright. Soon after, NASA satellites began to detect a large spike in absorbed solar radiation — the amount of solar energy that gets stored in the earth system instead of being bounced back into space. Also at around the same time, the part of the ocean with the most maritime traffic —the North Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico in particular— started to heat up rapidly.

The physics here are painfully straightforward: clouds are white. White things are white because they reflect light, but also heat. Oceans are dark; dark things absorb heat. That reducing cloud cover over the ocean should result in a hotter ocean is exactly as surprising as that you should feel hotter when the sun is shining directly on you than when it’s hidden behind a cloud.

Research now suggests as much as 80% of the short-term spike in planetary heat uptake since 2020 can be accounted for by the new cleaner shipping fuel standards. That’s big. And the effect is concentrated on the places with the busiest shipping lanes: the North Atlantic, in particular, has seen a very large spike in radiative forcing since 2020, estimated at 1.4 watts per square meter, according to a paper by researchers at NASA and the University of Maryland. (To give you a sense of scale, total radiative forcing worldwide from carbon dioxide since 1750 is estimated at 2.16 watts per square meter…1.4 is a big shock.)

Of course, climate is always complex, correlation is not causation, and you can never quite rule out plain old natural variability as a source of some of the rise. Research in this area is ongoing —thank God for that!— and no scientist is saying we can prove a one-to-one causal relationship between the new IMO regulations and the North Atlantic temperature spike that followed.

But none of the other drivers of absorbed solar radiation seem to fit the data. Solar output can’t account for it. The Pacific Decadal Oscillation should, if anything, have pulled temperatures in the other direction. Greenhouse gasses will, of course, heat both the atmosphere and the oceans, but they’ll do so gradually, over a period of decades. What we’re seeing isn’t that: it’s a sharp discontinuity that just happened to hit right after we withdrew a bunch of cloud cover from the North Atlantic.

If you’re acquainted with the literature on climate intervention, you’ll recognize this for what it is: termination shock.

One argument often given against climate intervention is that if you start doing it and later change your mind and stop, you risk termination shock: a sudden sharp spike in temperatures. That seems like a fair description of what’s happening right now.

Without quite meaning to, we conducted a huge geoengineering trial out over the oceans for several decades, then suddenly terminated it in 2020.

It was a particularly stupid, ill-conceived experiment, using a toxic source of cloud condensation nuclei. It would never have passed Institutional Review Board. It increased cloud cover and tamped down ocean temperatures by accident, not design.

Nobody in their right mind thinks we should go back to high sulfur maritime fuels. If we’re going to do this on purpose, rather than by accident, we’re much better off doing it with a harmless aerosol like sea-salt.

But this whole discussion does make a point that’s too often missed.

Marine Cloud Brightening isn’t some wild new idea a lunatic in a lab came up with.

It’s what we’ve been doing. For decades.

All of a sudden, we stopped...and the climate went haywire. Isn’t that a good reason to think we might want to do it again, but better?

It makes me wonder if much of the warming of the last 50 years is due to reduced air pollution. We burn much less coal in the northern hemisphere than we once did.

Interesting article, well reasoned by Quico (as always). There is just one thing I don't understand. When I look at the satellite picture of the ship trails, it reminds me very much of airplane condensation trails. There have been numerous articles in the press over the last couple years on the WARMING effect of contrails. Why is the effect of these ships tracks the opposite, cooling instead of warming?

Edit:

Just found my answer in the following article:

https://www.imperial.ac.uk/news/242017/clouds-created-aircraft-have-bigger-impact/

In a nutshell:

Ships produce a lot of aerosols but typically emit them low in the atmosphere – this changes clouds near to the Earth’s surface, making them brighter and creating a cooling effect.

Clouds formed from aviation are high up (10km up in the troposphere), and are very cold, making them good at stopping heat leaving the Earth and keeping it warm.

Not an easy story to sell to the public...