The Basketcase Exception

Some developing countries have bucked the trend and reduced their greenhouse gas emissions. You wouldn't want to live there.

The basic driver of GHG emissions trend — the fact that they’re rising fast in poor and middle income countries— isn’t universal. There are exceptions. It’s just that, when you do find an exception, it’s never the result of clearheaded environmental policy-making. It’s pretty much always because things have gone drastically wrong in that country.

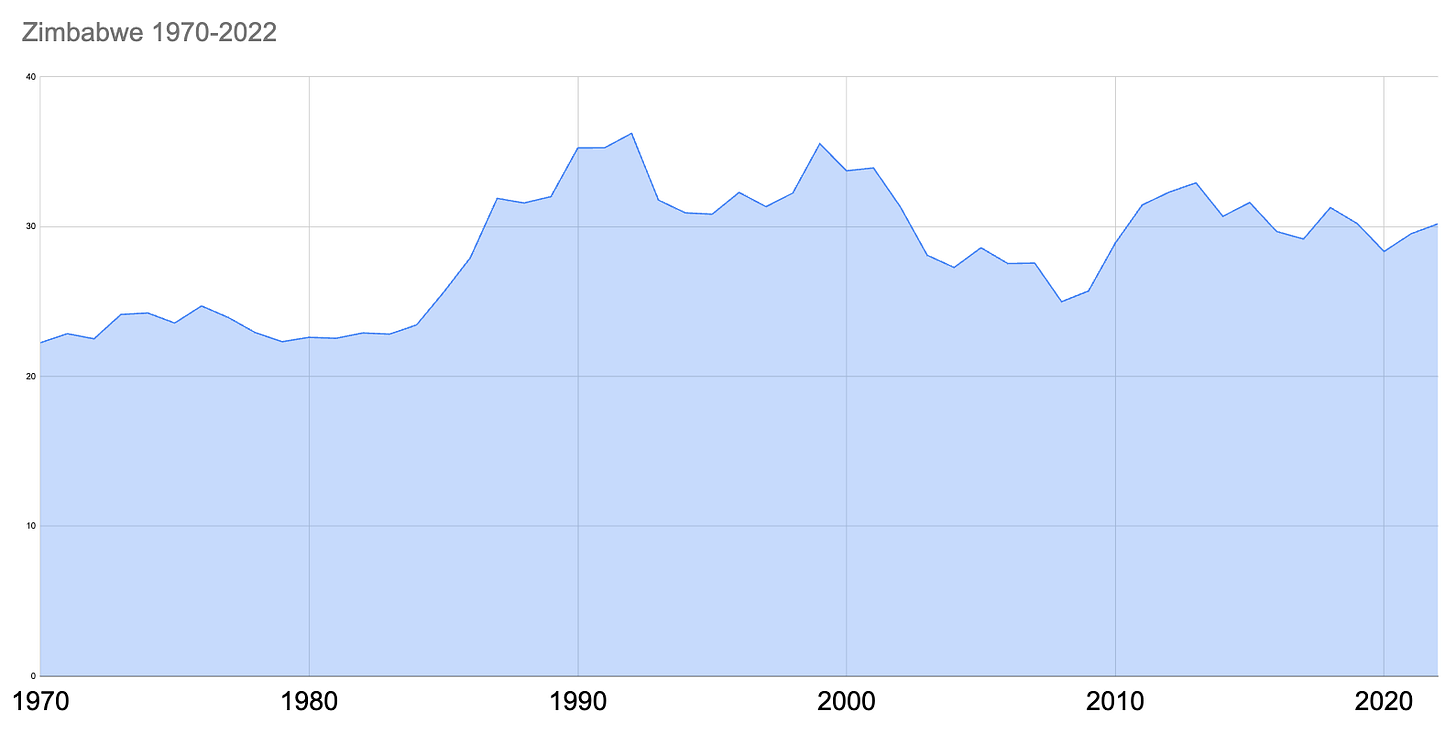

We’re talking about countries struck by hyperinflation and literal famines, like Zimbabwe, which now emits a bit less greenhouse gas than it did in 1990.

Where you see GHG emissions falling fast, your first guess should be that you’re looking at a place undergoing a severe political and economic crisis.

We’re talking about brutalized societies like my original country, Venezuela, where things have gone so drastically off the rails that a fifth of the population has had to literally flee since 2015:

It takes a world historical shitshow to drive quick sudden falls in greenhouse gas emissions of the type we’re being told we must engineer worldwide.

A thing on the scale of the collapse of the Soviet Union:

These are among the least desirable places to live in the world: countries plagued with life crippling levels of corruption, authoritarianism and political dysfunction. The kinds of places people will risk their lives to flee from.

So sure, I suppose it’s theoretically possible to keep down developing country GHG emissions without blighting the prospects of an entire generation through things like nuclear, solar and hydropower. In practice, though, this isn’t what we see. In the real world, the developing countries that see emissions fall are the kinds of countries people are actively fleeing.