The Strategic Logic of Climate Repair

How to save the planet when you have no control at all over two-thirds of greenhouse gas emissions.

There’s a baby in a bathtub.

Three pipes are pouring water into the bathtub.

If the water keeps rising, the baby is going to drown.

You can reach one of the three valves that control the flow of water. Your valve is rusty, you have to pull on it with all your strength to get it to budge just a bit.

The other two valves you can’t reach at all.

What do you do?

This, basically, is what it’s like to be a first world climate advocate in 2022.

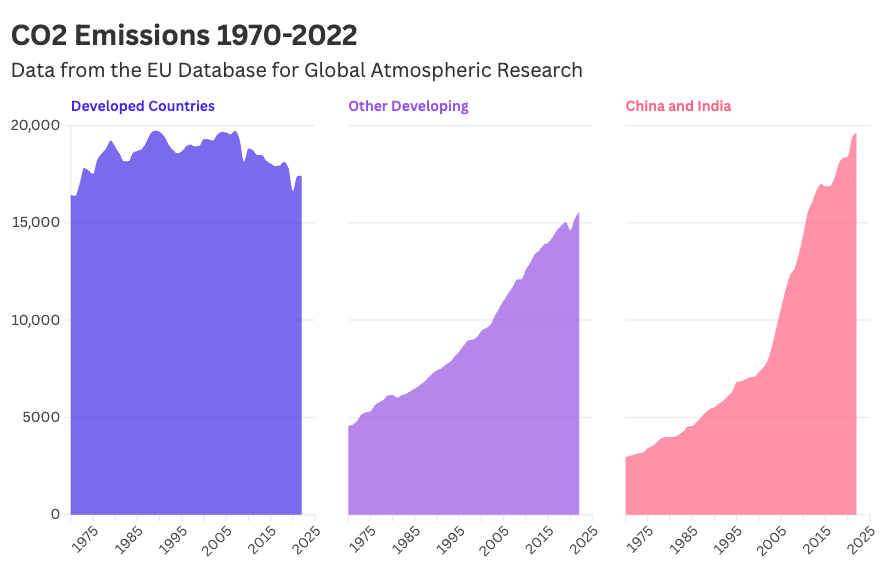

The first pipe, the one from Developed Countries, used to account for the bulk of climate emissions. Not anymore. Now it contributes about a third of the total, and that at a diminishing rate.

The pipe for the developing world, other than China and India, accounts for 30%, and it’s growing.

But the pipe pouring water into the tub fastest these days comes from China and India: 37% of the total, and rising fast.

What’s at stake? What does the baby stand for? Nothing less than the longterm human habitability of the planet.

You really don’t want to let that baby drown.

So what should you do? Should you work hard to close the one valve you’re able to reach?

Of course!

Is closing that valve a strategy to save the baby?

No, obviously not.

Strategy is just a fancy word for a plan that logically connects what you intend to do with the end-state you’re trying to achieve.

Closing the one pipe we have some agency over may be a good and virtuous thing, but it is not a strategy.

We can do it, we should do it, but we cannot save the baby by doing it.

Failure to see this subtly increases the already considerable peril the baby is in.

Because we have practically no leverage over the people who control those two other valves. And they face enormous pressures to keep those open. They see keeping their valves wide open as essential to their economic growth, their power, their well-being. You may disagree with them on that point, but that doesn’t matter a bit: they control those valves, you don’t.

A cold blooded assessment of the situation, then, shows that valve-shutting fails as a strategy to save the baby from drowning. This doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t do it. It means that if your focus is on the baby, you recognize that valve-shutting isn’t going to get you there.

Thirty-odd years of the UNFCCC have shown pretty conclusively that valve-shutting is not something humanity is able to do on the requisite time scale given our current state of technological and institutional development. We can (and will) get into long arguments about the whys and wherefores for this fact.

But it is a fact.

Does that mean we give up on the baby?

Of course not!

It means we have to think of creative new solutions for keeping the baby alive in a world that isn’t able to shut those valves fast enough.

Can we find some way to take the baby out of the bathtub? Can we get him into a floatation device of some sort? Can we think outside the box a bit, to find a strategy for keeping the planet habitable for the long-term?

This is the strategic logic of climate repair: decarbonization may be absolutely necessary, but it’s highly unlikely to be achieved on time. Three decades of the UNFCC have shown decisively that we cannot control the pace of decarbonization. We don’t have the institutions to do it, because there is no world government, and under international anarchy we can’t built the political consensus around it fast enough.

But there is something we can do. A set of levers we can control. If we want to save the baby, we better get serious about them.

Quico, a dramatic way to tell the story, while bringing out the realities and the logic. My one suggestion would be to say at some point, “The baby is us.”