Truth and the price of carbon

Dissecting the most confused number in climate

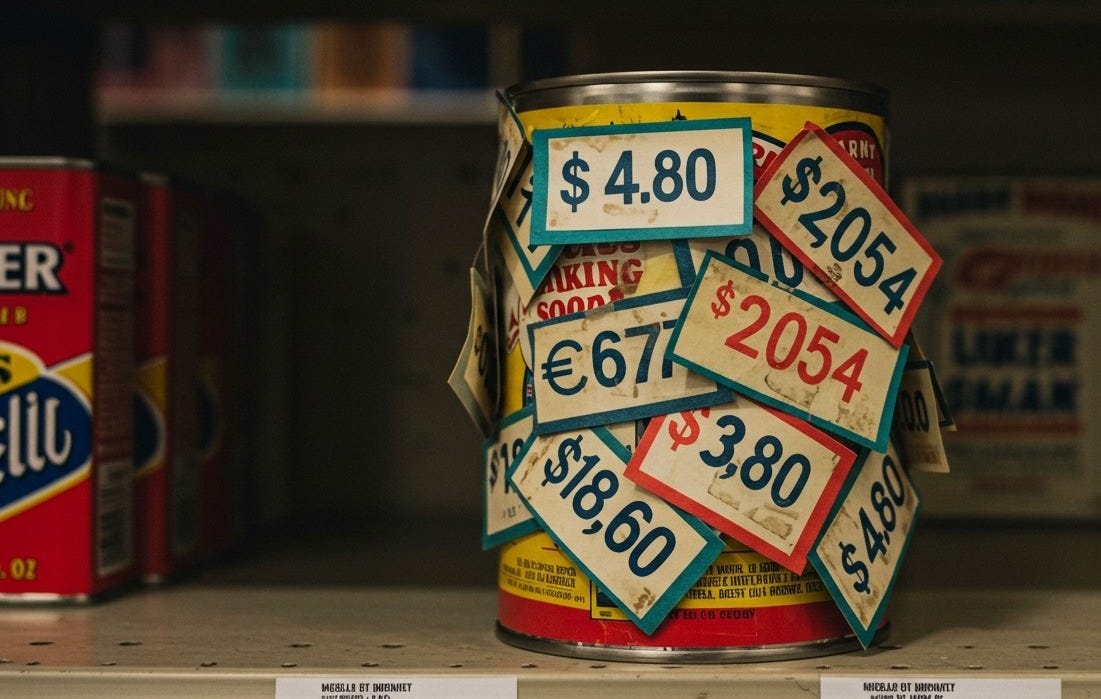

What’s the price of a ton of carbon dioxide ?

Easy: $4.80.

That is, if you’re preserving a forest.

Except, actually, it’s $118 if you’re growing trees and then capturing the carbon from burning them.

Though really it’s $2,054 if you’re running a fancy Direct Air Capture plant.

But not if you’re a polluter in Europe, in which case a ton of CO2 is €68.76, though not if you’re in China, where last year it cost $14.62, and certainly not if you’re in the shipping industry, in which case it’ll $380 starting in a few years.

But if you want to know what it ought to cost. Simple: $18.60. Or $280. Or $413. Depending on who’s doing the calculation.

Clear?

Clear as mud.

Dip your toes into the world of carbon pricing and insanity awaits. This is a world where is and ought are all jumbled up together, where optimistic projections fraternize promiscuously with verified realities, an upside down world where buyers seek out the most expensive options they can find and scorn cheaper alternatives. A total, total shitshow.

How do you begin to make sense of it all?

Carbon dioxide is what economists call a negative externality. People want energy, and carbon dioxide is emitted as a by-product of making energy. But CO2 messes up the climate, so it imposes costs on society that the people who generate it don’t pay. The costs are “externalized”: shoved off onto everyone’s shoulders.

Economic theory is pretty clear about what to do about externalities: if you can’t ban them, you should tax them. But because carbon dioxide messes things up at a global level, and there is no world government, there’s no public body able to tax it at the appropriate level.

That’s the institutional hard nub of the climate crisis.

Without a world government, you need to get sovereign states to cooperate towards a common goal. But that’s almost impossible, because each country faces overwhelming pressures to free-ride. (See also, 30 years of failed COP conferences.)

Without a world government, you end up with a patchwork of efforts to force companies to internalize the cost of carbon.

It’s messy.

Countries set up “emissions trading schemes” (what Americans used to call “cap-and-trade” schemes) that only operate within their own borders. The EU, China, South Korea, Switzerland, New Zealand and the UK each have their own system. California and Quebec operate an unlikely joint scheme, and Japan may soon get one.

The International Maritime Organization is developing an ambitious scheme to run something like this globally for the shipping industry, from 2030.

But these systems are all separate, and you can’t really trade carbon from one to the other. There’s no arbitrage, so prices don’t equalize. At best, these Emissions Trading Schemes are pseudo-markets — they try to capture the efficiencies of true markets, but do so only partly, and not very elegantly.

There are a bunch of reasons. First, because the carbon vouchers that get traded are figments of the bureaucratic imagination: issued by regulators to industry players on the basis of criteria that purport to technocratic impartiality but are ultimately pulled out of officials’ butts. Allocation is always the object of intense lobbying, giving rise to not-really-markets managed by officials who have to weigh the needs of economic efficiency and industrial stability against the environmental priorities they’re meant to be serving, all against a backdrop of intense political influence peddling.

It’s…not neat.

Look, I don’t want to be too cynical. The only thing worse than an emissions trading scheme is not having an emissions trading scheme. Some sort of price signal does come through these mechanisms. Companies that have excellent economic incentives to pollute more pay for the privilege of doing so, buying credits from companies that have found cheaper ways to clean up their act.

Remember, these are all schemes to discourage emitters from emitting. Bizarrely, they’re disconnected from schemes to remove the carbon dioxide already in the atmosphere. In most cases, companies in an ETS aren’t able to buy Carbon Dioxide Removal credits from outside the scheme. This cuts off a source of funding that Carbon Dioxide removers sure could use, and ends up undermining the economic rationality of the whole set-up.

Besides there are massive, massive holes. The U.S. has no mandatory scheme at the federal level, neither do Canada or Australia. Across Latin America and Africa you find a big desert, with a pilot scheme here, a voluntary scheme there, but nothing very substantial. South Asia and South East Asia have dabbled, places like Thailand and India are considering things. Overall, across shocking swathes of the world, schemes with teeth are the exception rather than the rule.

This gravely fragmented institutional picture is the reason carbon prices are all over the place. And that’s before you even get into the true horror-tale of the Carbon Pricing world: the arcane academic fight over the social cost of carbon —roughly, the dollar figure worth of damage that a ton of carbon in the atmosphere causes— much less the bedlam that is the voluntary market for carbon dioxide removal credits, which moves dollars out of donor pockets and into carbon removers’ at every imaginable price point.

I’m not going to say much about the social cost of carbon because that’s become an academic discipline in its own right, and one I’m not really qualified. I will say, though, that periodic press accounts of one research group or another’s finding that carbon should cost this or that much only add confusion to what is already a terribly confused public discourse, an ungodly mixing of is and ought that leaves you no one the wiser.

Outside cap-and-trade, in the “voluntary market”, there are no real market mechanisms in play at all. This is where most of the action is in the U.S. And the picture that emerges is not pretty.

The voluntary market doesn’t really deserve the name. In a real market, suppliers compete on price: if you can undercut your rivals, you can take up more and more marketshare. But in the carbon removals “market”, a series of perverse incentives send buyers searching for the most expensive credits.

Why? Because the buyers are basically all Corporate Sustainability departments, whose priority is to make the company look good. They know that 1,000 tons of uncontroversial, safe, thousand-year CO2 removal are a safer PR investment than 1,000,000 tons of CO2 removed for a less certain period, or through a method that creates any perception of risk at all.

Naturally, those uncontroversial, safe, thousand-year CO2 removals are hella expensive, so companies can’t afford very many of them. The sector ends up mired in small(ish) projects that generate rounding-error type removals: safe, uncontroversial, unlikely-to-lead to scandal removals that won’t really do a damn thing to move the needle on climate change.

Paul Gambill’s done the best writing about how the voluntary market got into this impasse, and you should go read it.

For now, though, I’ll close with just one thing: to become relevant at the huge scale climate operates at, carbon removal markets need to operate more like normal markets. Markets where cutting costs is a virtue, not a sin. Markets where buyers prefer to buy more cheaper credits , rather than fewer more expensive ones. Markets where traders can arbitrage price differences away.

Without those sorts of normal market dynamics, carbon dioxide removal can’t scale. Stuck at megaton scale, it will remain what cynics accuse it of being: a greenwashing exercise of little real relevance to the climate crisis.

Thanks for the vivid description on the cost of carbon. However the reason to buy expensive durable carbor removal is to Kickstart technologies that will become cheap in future. it has very little to do with how many tons are removed today and all about supporting R&D and development of new Solutions.

Interesting post and thank you so much for sharing.

Is anyone aware of serious projects focused on ensuring the fungibility of different carbon credits types, so that one can easily convert X credit type A into Y credits of type B, depending on carbon content, storage period, social welfare attributes, etc?

It seems like this would be a requirement to allow carbon credits markets to work (and, indeed, compliance markets are a lot closer to that, but they achieve that by forcing a single standard on all participants).