What we’re doing for the climate won’t work, here’s what will

Unlearning the zombie climate ideas so we can learn better ones

Electrify everything; embrace renewables. That, in four words, is the consensus approach to the climate crisis. It’s the dominant paradigm at the core of almost every big climate initiative worldwide: the UN Framework Convention on Climate change, America’s Inflation Reduction Act, Germany’s Energiewende, the EU’s Green Deal, Japan’s GX transformation, Britain’s head-first lunge into Net Zero.

It doesn’t work.

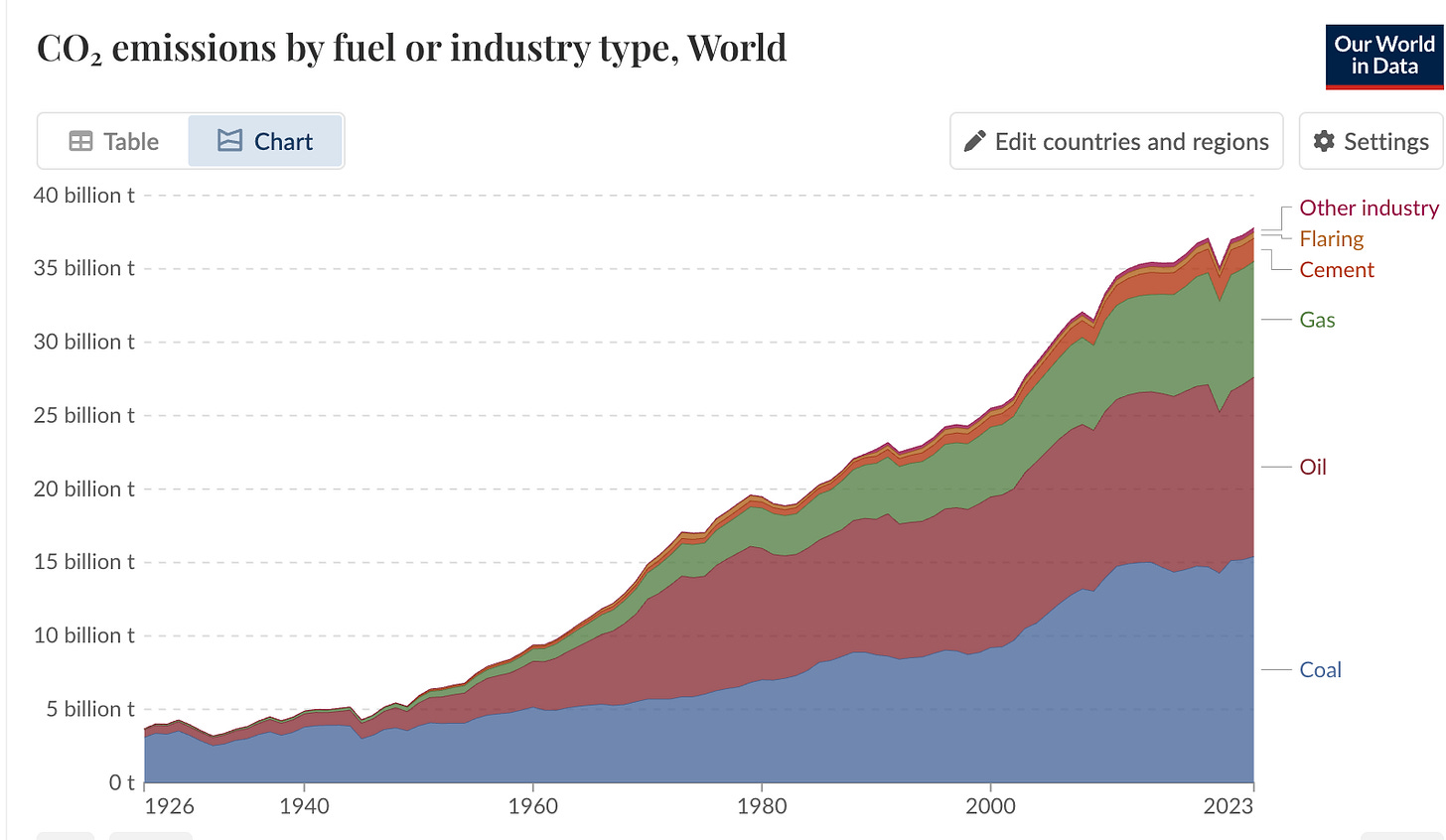

It obviously doesn’t work, in that emissions keep rising, year on year, at an accelerating rate.

It obviously won’t work, in that nothing new is being proposed, and what’s been tried until now has already failed.

It’s a consensus animated by dead ideas that don’t know they’re dead.

That’s why I think of it as a zombie paradigm.

And yet it remains dominant, and criticizing a dominant paradigm is always perilous. Paradigms become dominant by controlling the terms of debate, defining what is and what is not acceptable to be said.

Our zombie climate paradigm defines anyone who questions it as a denialist. So, I’m already suspect. Probably shilliing for an oil company, you’re thinking, or some denialist political project peddling the fantasy that climate change is no big deal.

Well, no.

Climate change is an enormous deal. We’re playing Russian Roulette with the gun pointed at our children.

We need to find an effective way to fight it.

But we can’t do that if we stay wedded to a zombie consensus.

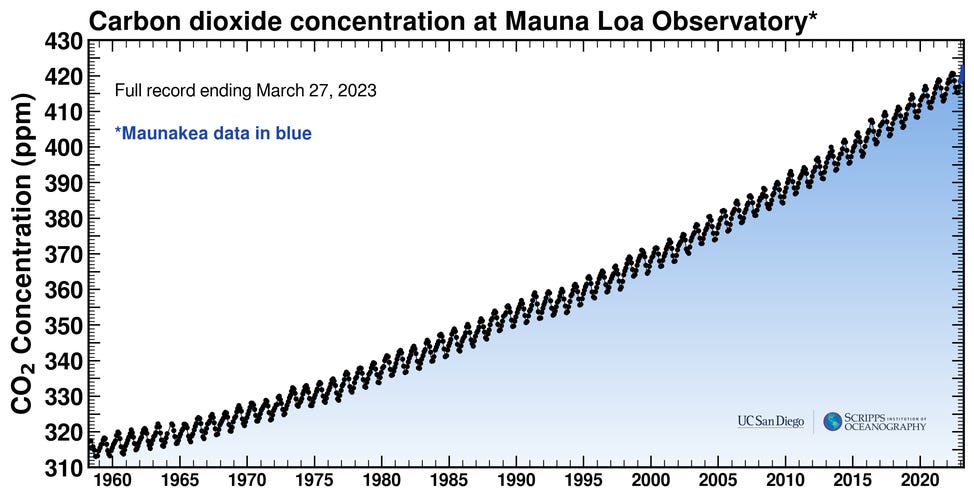

“Electrify everything; embrace renewables” won’t work for several reasons. The biggest is that it’s just too late. Maybe if we’d managed to stop adding new carbon dioxide to the atmosphere within five years of the first Earth Summit, it might have made sense. Back then, atmospheric CO2 concentrations hadn’t hit 370 parts per million, and you can imagine a stable climate at something close to that.

But for each of the 31 years since that first Earth Summit, we’ve continued to pump more and more CO2 into the air. With the sole exception of COVID-struck 2020, the rate at which we’re polluting keeps accelerating. We’re now well above 420 ppm, flirting with 430: far, far outside the range of a stable climate.

And it gets worse.

The full impact of atmospheric carbon dioxide takes a few decades to work itself through the climate system, the planet would continue to warm for several more decades even if we stopped polluting right now. Which, obviously, is not remotely in the cards.

The zombie paradigm has a clear prescription for what to do to fight back: go all in on wind and solar. But contradictions abound: we keep being told they are the cheapest energy source there is. And that’s true, unless it gets dark, or the wind dies down. At grid scale, it turns out, they tend to be expensive and unreliable — and as their share of generation climbs, those problems amplify.

The zombie paradigm has left us in an absurd situation, where countries spend hundreds of billions to subsidize energy sources we’re told ought not to need subsidies at all (isn’t it already cheaper than fossil fuels?) In return, we get energy that’s more expensive, more volatile and less reliable.

Voters have noticed. And they don’t like it.

“Electrify everything; embrace renewables” is not working, because it’s the product of ideological thinking blind to thermodynamic realities. It has already failed comprehensibly as a strategy. But it’s so dominant in climate conversations that we struggle to see outside of it.

The paradigm is dead. Or rather, undead, because nobody’s informed it that it’s dead, so it just keeps going. Climate activists keep supporting it, and treating anyone who questions it as an enemy. It’s pretty grim. Those who question it are mostly cranks and denialists, which suits the movement just fine, because it exempts them from really taking stock about how badly the paradigm is failing.

So is this just a doomer’s lament? Are we just fucked, with nothing else left to say?

Not at all.

This is a call to get real.

A call for a serious, even-keeled rethink, that looks at the entire problem from first principles and looks at the whole range of avenues open to us.

Because we are not helpless. We have options. When we stop bullshitting ourselves, we can start a too-long-delayed discussion of strategies that have much higher chances of success than what we’ve been doing. Which, honestly, is not a high bar, because electrify everything, embrace renewables has zero chance of success.

So what pithy, four-word formula can replace “electrify everything; decarbonize electricity.” I think I have one. One that depends neither on technological miracles nor far-fetched geopolitical reallignments:

Capture carbon; embrace nuclear

Thirty years ago, focusing on emissions, might have made sense. At this point, we’ve emitted so much that a realistic approach to climate change has to deal with the stock of carbon dioxide already out there.

The total is now terrifyingly large —something close to 3.3 trillion tons of CO2. Focusing on slowing the rate at which we add to to that giant pile misses the point. That ship has sailed. The challenge for the next generation is to actively reduce the stock of atmospheric carbon diooxide.

Which means we need to get serious about capturing carbon, gigatons at a time.

The received wisdom is that this is impossible — many orders of magnitude too expensive to do at scale.

The received wisdom is that, at best, we can afford to capture a few hundred tons by planting a forest here, a few thousand tons with a Carbon Capture and Storage project there, nice gestures all, but nothing like the billions or tens of billions it would take to put a dent in the total.

The received wisdom is that these projects tend to be either short-lived or far too expensive — costing hundreds if not thousands of dollars per ton of CO2 captured.

The received wisdom is wrong.

Carbon dioxide removal for less than $10 a ton is possible. And if we’re smart, we’re going to focus ruthlessly on achieving this goal.

The most promising avenue to achieve it is ocean photosynthesis. Light-eating marine micro-organisms (phytoplankton) are insanely good at capturing CO2. Stimulating their growth costs shockingly little. We’re definitely not going to run out of ocean to grow them in. But they’re not the only option. Macro-algae —seaweed to you and me— is another ocean photosynthesis avenue that could capture carbon at climate-relevant scale quickly and affordably.

I spend most of my time working on those approaches. Somebody somewhere is going to figure out a cheap way to get thousand-year sequestration down below $10 a ton, and I’m convinced that someone will be working with ocean photosynthesis.

The first and most important rethink a new climate consensus needs to build, then, is around investing serious resources in better understanding marine Carbon Dioxide Removal through photosynthesis. The mismatch between the amount of funding going into this work, and the sums going into, say, new solar installation subsidies is genuinely bizarre and self-defeating: a testament to the ongoing grip the Zombie Paradigm has over our climate conversation.

Of course, ocean photosynthesis is not a magic bullet, getting it right will require careful study and sustained research. But it does look like the cheapest, safest, most scalable carbon dioxide removal avenue available to us.

In a way, it’s strange that focusing on large-scale carbon removal is controversial. The IPCC has known for years that we’re on track for substantial climate “overshoot” — we’re now almost certain to exceed the 1.5 degree warming goal in the Paris Agreement. The only way to return to a stable climate once we’ve overshot is to take emitted carbon back out of the atmosphere.

We’re already, technically, committed to doing this: blue-ribbon commissions led by members-in-good-standing of the global elite are on the job. But we seldom talk about it, because it’s an awkward fit with the consensus on “electrify everything, embrace renewables,” and the pull of the Zombie Paradigm is so great that it renders even the things we’re committed to unmentionable.

Still, the international community has already accepted the necessity of large-scale carbon capture. And we’ll be much better off if we do it sooner than later. Waiting to hit a planetary tipping point before acting would be insanely irresponsible. If we can put ourselves in a position to capture multiple gigatons of carbon dioxide per year and store them safely in the ocean by, say, 2035. We’ll be much, much closer to a safe climate.

The good news is that we’re not that far off scientifically. One company is already using phytoplankton to capture carbon. Many researchers are looking into it. Nature itself is already doing it: undersea vents show pretty conclusively that increasing carbon capture in the ocean is safe, cheap and effective.

What’s lagging is public awareness of this avenue’s unique potential, and donor willingness to support the work at a reasonable level.

Capturing carbon at scale would buy us precious time to decarbonize our energy systems. But we will still need to do that. It’s just that we’ve been going about it all wrong.

Like soft-headed fools, we’ve gone all in on techniques that give us a warm, fuzzy feeling and look nice on a Powerpoint. There’s a much better way.

Because decarbonization is a problem with a known solution.

The “energy trilemma” — security, affordability, sustainability— is bullshit: with nuclear, you get all three.

Yes, nuclear too

Decarbonization via nuclear energy isn’t just some theory. It’s the every day reality in places that had the foresight to go big on nuclear a few decades ago: France, Sweden, Finland and Ontario have some of the world’s cheapest, most reliable, least polluting power grids.

If anything, focusing on successful cases from the past downplays the transformative potential of nuclear energy. Because quietly, nuclear technology has gotten much better since those countries built out their nuclear generation fleets.

It’s hard to notice, because we’ve stopped building new reactor designs. So our image of nuclear power is stuck in 1970s amber.

But think how much technology has changed since the 1970s.

We have much better advanced composite materials than the Swedes and Ontarioans had in the 60s, much better simulation software and compute than the French had in the 70s, much more efficient reactor designs than the Finns had in the 90s.

The way my boss sometimes puts it, comparing advanced 21st century reactor designs to legacy reactors is like comparing a 1975 VW hippie bus to the a new-generation VW camper.

People think we’re trying to sell them this:

Obviously they don’t want that, because that technology is clunky, unreliable, unsafe, uncomfortable, slow and hugely polluting.

But we’re not in 1975!

What’s on offer looks more like this:

The same kind of thing, but superior in every way: much safer, much more reliable, much less polluting, much more comfortable, much faster, much better in every way.

Next generation nuclear reactors are defined by passive safety design: no human being has to lift a finger for them to operate safely. They are “walk away safe”: even if every single plant operator at the plant somehow dropped dead at the same time, the reactor would just power down safely on its own due to the intrinsic physics of the way it works.

New reactor designs are also far more efficient than their old-timey counterparts, meaning they generate a tiny fraction of the waste of legacy designs. Some are designed to generate their own fuel as they operate and hardly ever need refueling. A few advanced reactor designs are so good at reprocessing their own waste internally and using that as fuel, that some people argue we should go ahead and slap the label “renewable” on them: it would take hundreds of thousands of years in operation before we run out of fuel for them. Safely storing the miniscule amount of long-term radioactive waste new generation reactors generate is not a difficult engineering problem.

The best new designs don’t rely on water as a coolant at all, which means they can run at 500, 700, up to 1,000 degrees celsius, meaning they output industrial heat far more cheaply than electricity can. Advanced nuclear can decarbonize not just electric grids but things like cement-making, steel-making and industrial chemistry in a way weather-dependent renewables simply can’t.

If we got over our shit, we’d realize the world-changing importance of this: we already have a safe, zero-carbon energy power source source with a miniscule environmental footprint.

If even the old, clunk 1970s-vintage reactors they run in France and Ontario have proven you can decarbonize affordably, imagine what you could do with 21st century technology. The advanced reactors on offer now could be mass produced, making the power they generate an order-of-magnitude cheaper.

Which means reliable, cheap, zero-carbon energy abundance is there for the taking.

In a world where voters won’t stand for climate solutions that compromise energy reliability or affordability, nuclear is the no compromises solution. We could, tomorrow, decide this is the future we want. We could approve smart regulations to make it so, roll out better financing models to recognize nuclear mitigation outcomes pari passu across technologies, and start building out the nuclear fleet of the future.

Which is why, despite everything, I’m kind of optimistic about the climate. Because the solutions are at hand, we just have to embrace them.

The problem, really, is cultural: the grip the Zombie paradigm still has on this conversation.

We’ve grown so used to equating “fighting climate change” with “electrify everything; embrace renewables” that we struggle to think outside that box.

But paradigms do shift. And this one better. Because future generations won’t forgive us if it doesn’t.

Another great piece. Your strategy makes sense. Of course, the elephant in the room is that that many boomers, who spent years or decades campaigning against nuclear power [which even half a century ago was the cleanest, safest energy] don't want to admit that their paranoia caused a massive setback to their own environmental efforts. And of course politicians only like solutions that result in crony subsidies--but I'm still mystified about why so few politicians realize that the nuclear industry is where the smart investments are.

Outstanding post. Please keep up the good work.