Where are we with Greenhouse Gas Emissions, really?

Two inconvenient truths in three sly little charts

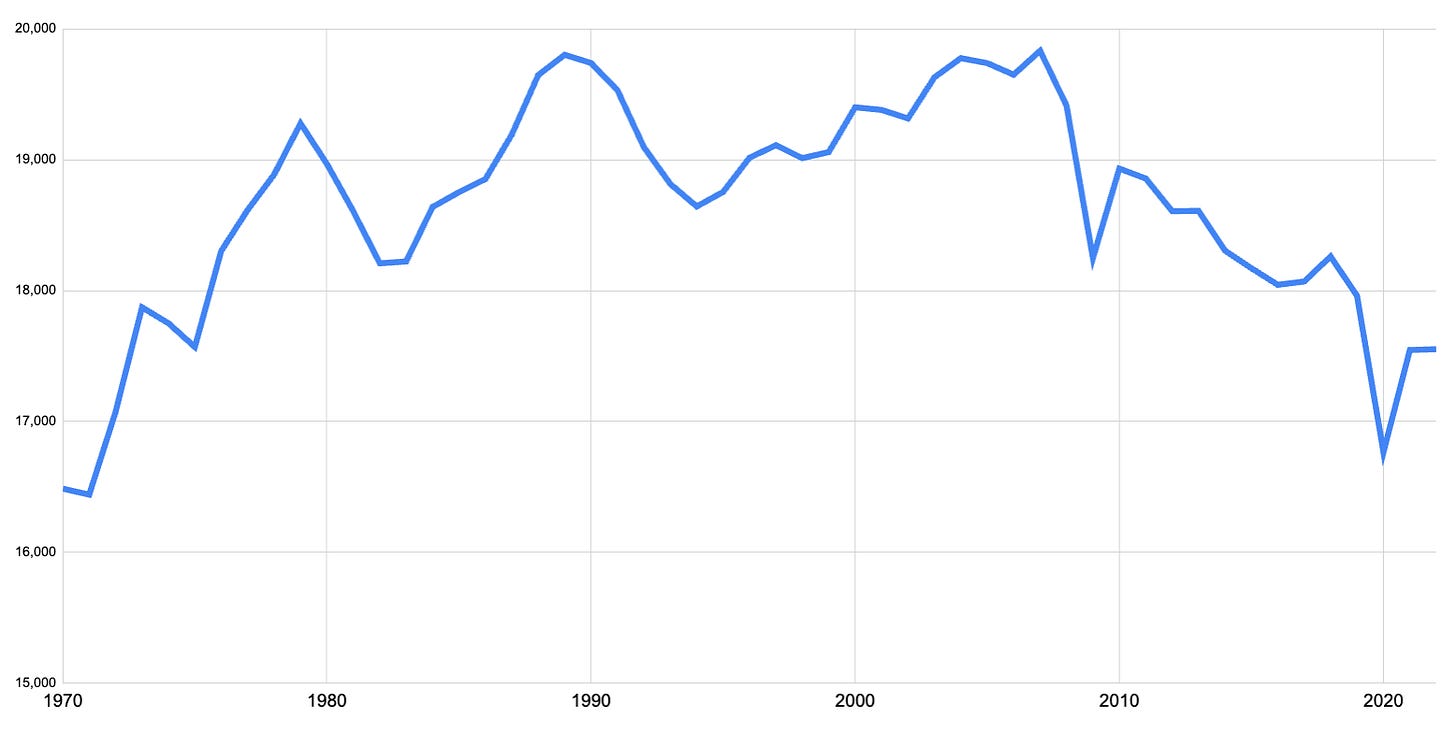

You might not know it from the discourse, but the reality is that our greenhouse gas emissions have been falling, quite considerably, for some time now.

Emissions now are 13% lower than at their peak in 2007, when we emitted almost 20 billion tons of CO2 equivalent. That figure’s dropped to 17.6 billion tons as of 2022.

The energy transition may not be proceeding as fast as we’d hoped, but evidence of decarbonization is plain in the data from the EU’s Database for Global Atmospheric Research:

Nonsense!

Emissions have exploded since 1970.

Aside from a barely perceptible downtick during the pandemic, they’ve just kept going up and up and up for the last six decades.

The trend is unmistakable, and very marked: we’ve gone from emitting just 7.5 billion metric tons of CO2 equivalent back in 1970 to more than 35 billion now, and there’s simply no sign of the energy transition anywhere in the data.

Just look:

Wait, what’s going on here? Which of these is right?

They’re both right.

The first chart captures emisssions from the developed world, the second from the developing world.

This is what they look like together:

In the 21st century, a modest fall in emissions from the rich countries has been overwhelmed by an explosion in emissions from the developing world. In fact, all of the growth in emissions this century has come from poor and middle-income countries like the one where I grew up.

As of 2022, the developing world emits about twice as much GHG (35.1 billion tons) as the developed world (17.6 billion tons.)

China by itself emits 15.7 billion, nearly as much as all the developed countries combined.

All of the rest of the developing world accounts 19.4 billion tons of CO2 equivalent.

This basic picture really should be driving the entire debate about climate change, but it makes us uncomfortable, so we rarely acknowledge it.

Really, try asking the next 10 climate-aware people you meet to guess the rough breakdown between developing and developed country emissions and trends and see what they say. In my experience, even climate heads just don’t know.

We don’t talk about it in part because it feels unfair: the vast bulk of cummulative emisions going back to the dawn of the industrial revolution have indeed come from today’s developed countries. On the overall global guilt-o-meter, the developed world still clearly bears the bulk of the blame for the mess we’re in.

As it happens, the atmosphere is serenely indifferent to historical responsibility. A molecule of carbon dioxide emitted by a Manchester sweatshop in 1858 absorbs infrared radiation at precisely the same rate as one emitted by an Indonesian motorcycle yesterday.

But I suspect there’s another reason we’d rather not process this reality. The relative irrelevance of developed-country emissions suggests an intolerable reality: the future of the planet is not in our hands. It’s not in the hands of our politicians, our companies or our citizens. It’s in their hands.

The decisions that matter to the future trajectory of emissions won’t be made in Berlin, New York or Tokyo. They’ll be made by electric utility officials in Bangkok and Addis Ababa deciding how to build out their grids. By politicians in Mexico City and New Delhi, deciding whether to tax or subsidize their hydrocarbons. By oil company executives in Saudi Arabia, Indonesia and Brazil trying to allocate their exploration budgets.

While we exhaust ourselves on trivialities about Taylor Swift’s flight schedule as we fiddle with the paper-straws we’ve been told will help save the planet, the decisions that lock in off-the-charts heating are being made by people in faraway places who don’t get our memes.

They respond to incentives we don’t understand in contexts we have no idea about, and we have absolutely, positively no control over them.

And that scares us more than climate change.

The developed world has more influence than you suggest in the levels of greenhouse gases emitted by the less developed world.

availability of low cost financing from multinational organizations like the World Bank , direct aid from developed countries, technology transfers and other political social and economic influences are all important determinants of climate pollution in less developed countries.

You are correct that most Climate aware people are not cognizant that the key decisions will be made in capitals of countries far away. But those decisions can be significantly influenced by determined efforts from developed countries.