Apocalypse later

How much is it rational to spend now to avoid a climate calamity in the 22nd century?

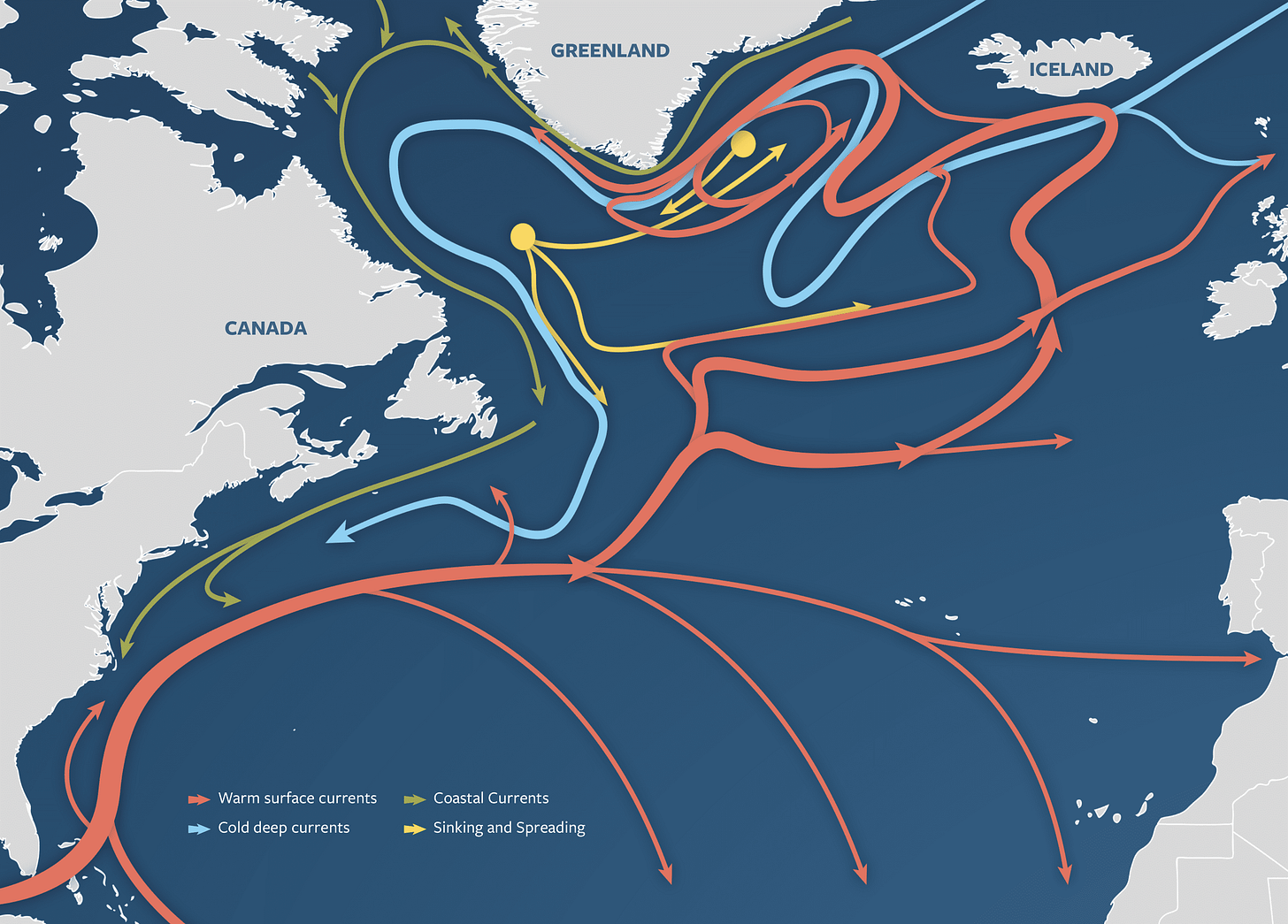

London is as far north as Calgary, but the two cities’ climates are nothing alike. The reason, your high school teacher once told you, is the warm ocean current known as the Gulf Stream, part of a broader ocean circulation pattern known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC to friends.

Climate scientists have been warning us for years that AMOC is in trouble: once ice loss from Greenland reaches a certain threshold, the circulation patterns that keep Western Europe relatively comfortable could go into irreversible decline.

How near we are to that tipping point remains hotly contested. What’s not contested is that crossing it would be a civilization-blighting calamity.

But here’s a question you probably haven’t heard nearly so much about: how long, exactly, might it take for AMOC to wind down after it enters its death-spiral?

This turns out to be super tricky to model. But I was staggered to learn scientists expect the process to take more than a century, perhaps as long as three centuries.

Which means the Londoners who’ll actually face Calgary-style winters are not the ones alive today, but more likely their great-grandchildren, if not their great-great-great-great-great grandchildren.

This isn’t a secret, exactly.

Researchers who work on AMOC understand it very well. It’s just in no one’s political interest to call attention to the fact. Tell people frankly that they’ll be long gone by the time AMOC collapse really bitesand it becomes much harder to persuade them to do something about it.

The trouble is that it’s not just AMOC. Across the climate board, the really catastrophic results are likely to fall on people who haven’t been born yet.

Politically, this is terribly awkward.

In our narcissistic age, climate activism has become obsessed with playing up the immediacy of climate threats. That’s why we keep being reminded it’s a climate crisis. Nobody trusts us to make difficult decisions now to prevent harms far off in the future.

Witness the whole benighted field of weather attribution: an openly politicized field of pseudo-science meant to convince people that whatever weather-linked disaster has befallen them personally is the result of climate change. Better substackers than me have debunked this non-sense more competently than I can.

Alas, there’s a parallel danger on the other side: the equally narcissistic tendency to think that if climate’s not a problem for me then it’s not a problem at all.

Guys like Roger Pielke Jr. and Chris Wright fall into this trap all the time — acknowledging, broadly, that climate change is real but implying the threat is so distant, it’s not really worth doing much of anything to mitigate it.

Surely that’s not right either.

Instead, climate change forces us to think seriously about intergenerational equity: what exactly do we owe people we’re related to but will never meet? What sacrifices is it reasonable to ask the people of 2025 to make on behalf of the people of 2125? Or 2225?

There aren’t any easy answers to those questions.

Or rather, there aren’t any precise answers. Because, on one level, the answer is perfectly obvious: less.

If you thought you needed to act now to prevent London from having Calgary winters starting next year, you’d obviously be much more inclined to incur major costs to prevent that than if the people who are going to be shoveling the snow are your great great great grandchildren.

That’s normal and, indeed, rational: we discount the future. Apply a reasonablish discount rates and you very quickly realize it’s not, strictly speaking, rational to spend a lot of money now to prevent even a big catastrophe 100 years from now.

Under exponential discounting, with a 5% discount rate, even a $100 trillion catastrophe in 2125 only merits a $760 billion worth of spending this year. (And we spend way more than that on climate mitigation — $1.9 trillion a year, at last count.)

Personally, I find the campaign to persuade people that climate is a looming disaster for them personally distasteful, because it’s fundamentally dishonest. It’s bad politics, too. Normies overwhelmingly reject climate scaremongering. They see it for what it is: an attempt to manipulate them into supporting policies that won’t make their lives better.

Trying to build political support on the basis of false claims is a dead end.

We’d be much better off fessing up: climate change is a civilizational threat, but the civilizaton it really threatens isn’t ours, it’s the civilization of the 22nd century.

Reasonable people can agree that we should take steps to prevent very bad harms to our descedents in the far future. By the same token, reasonable people will balk if you ask them to turn their lives upside down for the benefit of people they’ll never meet.

This tends to drive climate people crazy, because it seems so selfish. But it’s important to grasp that it’s not actually irrational.

By any reasonable estimation, the people of 2125 are going to be much wealthier than we are, far more technologically advanced, and much better able to adapt to whatever the climate throws at them. In intergenerational equity terms, asking us to bear the bulk of the cost of adaptation is sort of like asking Africans to bear the costs of mitigation today: an irrational shoving off of the burden on those least able to bear it.

Except it’s not actually that simple, because there are some mitigation actions that only our generation can take. Once the AMOC tipping point is reached, there’s no way to bring it back. We may be poorer than the people who’ll be around in 2125, but we can save AMOC and they can’t.

Still, the normative side of the question seems less relevant to me than the positive side: we know now, because we’ve already seen it, that voters act as though they understand the worst climate harms are in the far future, and they apply a relatively aggressive discount rate to those far-future harms. In acting this way, they behave a good deal more rationally than the climate alarmists urging them to degrow now to prevent far-future harms.

In a world where rational voters won’t support harsh costs to mitigate far-future harms, the challenge for us is to use the resources we do have as efficiently as possible. As we face the reality that the world’s collective willingness-to-pay to avoid climate harms is limited, it becomes even more important not to waste the resources we do have.

Climate budgets are unlikely to grow very much in the future, so we must demand value for money. To my mind, what this all means is clear as day: we need to get serious about low-cost carbon dioxide removal and advanced nuclear power.

People today are not being irrational when they say they are worried about climate impacts but also unwilling to impoverish themselves to avert them. We should recognize this as a rational response to a terrible incentive structure.

But if you go carrying pictures of Chairman Degrow, you ain’t gonna make it with anyone anyhow. Hectoring normies is always going to be terrible politics.

Actually, the citizens of Western countries may not be richer in a hundred years if we bankrupt ourselves now. The most prudent thing to do is allow ourselves to get richer and gradually reduce CO2 emissions by a rational switch from coal to gas and nuclear.

This is an interesting discussion. But for me it really DOES make me think we shouldn't do "much of anything" about it now. Imagine how we would currently judge scientists back in 1825 altering their own society to try to save their 2025 descendants from environmental "calamity" due to... I don't know, dwindling firewood and whale oil? We would think them laughably naive and child-like. Our descendants in 2225 will probably look on our expensive and inefficient "green" efforts now similarly, especially when they notice how haphazard and inconsistent those efforts are. What eventually helped us move on from those primitive fuels was industrial and technological advancement (which continues today), not by drastic cutbacks in energy consumption and quality of life.

Also, maybe it was just a single example, but you don't really make the case that London experiencing Calgary-like winters would actually be "civilization-blighting", especially if that change happened slowly over centuries. There are large, thriving cities with Calgary-like winters now, including, well, Calgary. Are Canadians blighted?