The Washington Post had it exactly backwards about air pollution and hurricanes

An unfortunate blunder, now corrected

*The article in question has now been corrected. Good!

Original post, for transparency’s sake:

First things first, climate-change-makes-hurricanes-worse discourse is generally pointless: extreme weather event attribution is an openly politicized pseudo-science that no one should take too seriously. The real stakes in the climate crisis are both much more serious and much longer term.

There’s something infantilizing about the media’s obsession with making climate change feel personal, a panicked sense that unless people feel threatened themselves, they won’t do anything. It’s a recipe for crappy journalism.

But there are levels of wrong, and this Washington Post piece about the supposedly increasing prevalence of Category 5 hurricanes is wronger than most.

Ian Livingston walks us through the trend, pointing at higher sea surface temperatures as the likely culprit. But why are sea surface temperatures rising?

Here, Livingston cites Michael Lowry, whom he identifies as “a hurricane specialist and storm surge expert at the TV station WPLG in Miami”:

Lowry said that “the increase in higher-end Atlantic hurricanes is consistent with what the research has shown us,” or that there are more frequent such events than in the past. He highlighted that there was an extended period in the 1970s and 1980s with low hurricane counts in the Atlantic, largely attributed to reduced pollutants, that probably helps mask an otherwise persistent longer-term upward climb.

Now, I dunno if Lowry mixed this up in his email or if Livingston straight-up didn’t understand, but this explanation is exactly backwards.

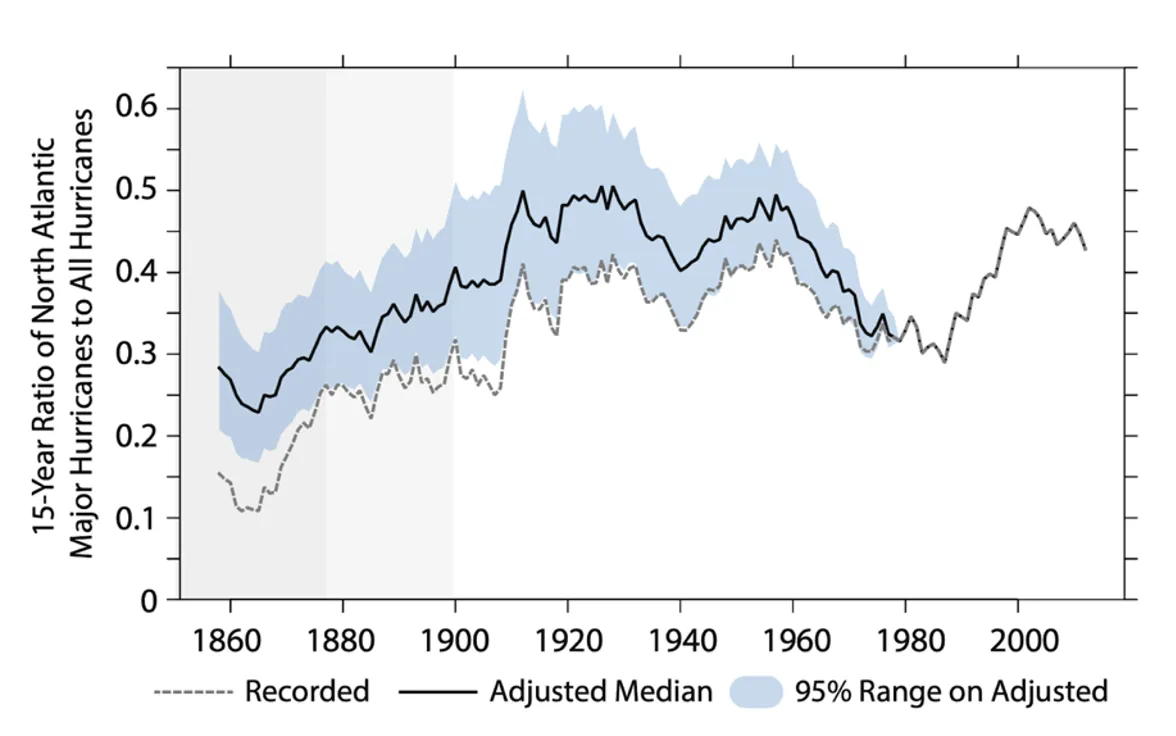

The 1970s and 1980s were an era of off-the-charts air pollution — and that pollution cooled sea surfaces by making the atmosphere more reflective. As new clean air regulations kicked in in the 1990s and 2000s, albedo decreased and sea surface temperatures started to rise. Quickly. That’s when the big hurricanes made a comeback.

This is very well known to climate researchers. But Livingston’s blunder speaks volumes. Because if he’d written that sentence correctly, he would have confused the hell out of his readers.

Say that the reduction in hurricanes in the 1970s and 1980s is largely attributed to increased pollution and you scramble all of your audience’s priors. All of a sudden, you have to spend the next four paragraph explaining something that feels dead wrong.

Your nice, clean, morally unambiguous narrative (pollution → hot seas → big hurricanes) is now an uncomfortable, messy, morally ambiguous nightmare. Now you have to get your audience to accept that the climate is complex, and sometimes the things you do to improve the environment one way mess it up in another way.

This, it is widely understood, is more than readers can handle.

Forty years of environmental education and climate consciousness raising have left us totally unprepared to understand the complexities of the climate system. Albedo, in particular, is systematically excluded from public discussion, even though all serious climate researchers know very well that changes in albedo are some of the strongest determinants of short-term climate fluctuations.

The result is this strange state where the more an average person reads mainstream press accounts of the climate, the less she understands about what’s going on. The gap between what scientists know about the climate and what is represented to the public as the scientific consensus about climate just keeps on growing.

The point about the 1970s–80s hurricane lull being driven by increased aerosol pollution is exactly right. Sulfate aerosols from mid-20th century industrial activity reflected sunlight, cooled the North Atlantic, and suppressed hurricane activity. As air-quality regulations in the US and Europe reduced those emissions in the 1980s–90s, the masking effect lifted and greenhouse-gas warming reasserted itself, driving sea surface temperatures (and hurricane activity) upward. This is well established in the literature (see Dunstone et al., Nature Geoscience, 2013; Murakami et al., Nature Geoscience, 2015).

Where I’d be more cautious is in calling event attribution “pseudo-science.” The field is indeed politicized at times in its presentation, but the underlying methods are rigorous: comparing model simulations with and without anthropogenic forcing to estimate how climate change shifts the probabilities and intensities of extreme events. The World Weather Attribution group, for instance, has published peer-reviewed studies on heatwaves, floods, and hurricanes using this framework.

So yes — media narratives often oversimplify complex feedbacks into neat morality tales. But that’s a problem of communication, not of the science itself.

Very glad you are pointing this out.