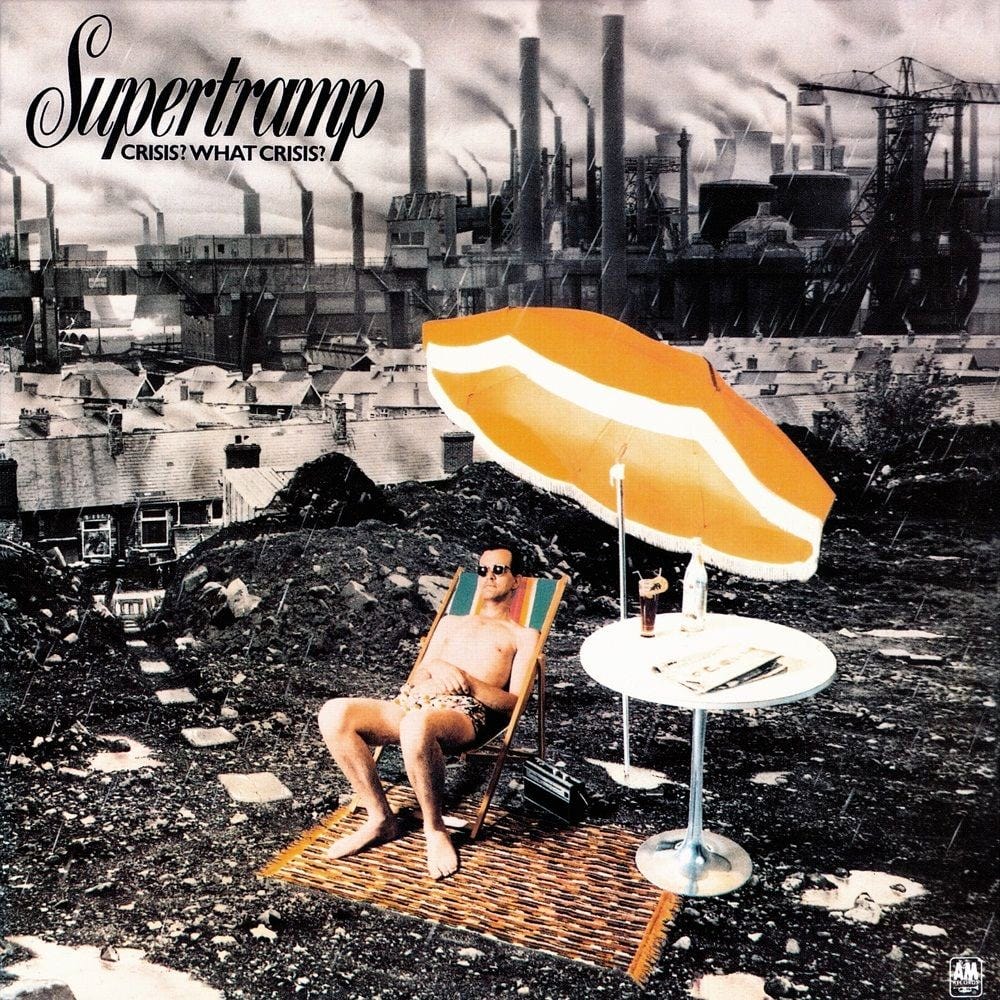

Yes, climate is a crisis. No, not for you.

How climate narcissism leads the green movement down a blind alley

Here’s a guess: you’re a reasonably well-off person in a reasonably well-off country.

I’m pretty sure that’s true, just because you’re reading climate substacks. You may not be rich, but you’re most likely not worried about where your next meal is coming from. Or the ten meals after that one.

If that’s right, here’s a reality check: climate is not a crisis for you.

You may have climate problems. Almost certainty, you have climate anxiety. But crisis? Crisis in the way, say, an imminent home invasion is a crisis? Or the way a cancer diagnosis is a crisis? Be real, now. That’s not the kind of problem climate is in your life.

Does that mean there is no climate crisis? That it’s all a big nothingburger?

Not at all.

The climate crisis is real. But the people for whom climate is a crisis are too busy weeding their sorghum plots in Bihar or Mali to waste time on substack. Either that, or they haven’t been born yet.

Desperate to drum up political support for climate action, rich country climate activists have devoted a lot of time and energy to making climate feel like an overwhelming problem for you. Grasping the deep narcissism at the core of contemporary first world culture, they’ve calculated —dismally, but probably not incorrectly— that unless they make it about you, you won’t lift a finger to help.

Climate narcissism —the vague sense that the climate crisis is only real if it’s a crisis for me— is the driving force behind contested scholarship about “weather attributions”: desperately seeking to make any and every disaster a function of climate change.

It’s at the core activist zeal of Extinction Rebellion is about. The view seems to be that people like you won’t do anything about climate until you feel personally threatened by it. From this point of view, jacking up the threat perception on the part of rich country voters is the overwhelming movement priority.

This agenda leads to the kind of climate catastrophism that turns normies against the climate movement. Sky-is-falling narratives mostly don’t land with regular people, because while the climate sure seems to be screwy these days, for most people most of the time it’s nowhere near screwy enough to seem like an actual crisis. The catastrophist agenda gets tuned out, because it feels dishonest to regular people. Because it is.

We’d be much better off just admitting that if you live in a rich country, and you’re not very poor yourself, you already have the tools at your disposal to manage the climate risks you face.

You can buy insurance, and if you can’t, you can move somewhere where you can. You can rely on relatively professionally run and adequately equipped public agencies tasked with managing disasters. You’re protected by well developed and enforced building codes to ensure resilient infrastructure. You are, at any rate, probably not living in one of the areas most exposed to climate disaster, and if you are, you can move. Climate may be a “crisis” to you in some sort of ideological sense, but to you it’s more like an inconvenience. A worry. A source of anxiety. But not, in any normal sense of the word, a “crisis.”

But if you don’t have all those layers of privilege, if you’re a poor person in a poor tropical country living on the edge of agro-ecological viability, then climate change might very well kill you. If you survive by farming one acre of sorghum and the variety you have can just about hang on at 41° C but will shrivel up and die at 43°, then climate change is life and death to you. Not in some high-fallutin’ rhetorical sense, but in the very specific sense that you’re not going to have anything to eat, and nobody’s going to come save you.

First world climate activists calculate that the appalling calamities climate change may bring to the world’s powerless won’t push people like you into action.

It’s sad to say, but they’re probably not wrong.

The world is, as we speak, sleeping through a genuinely garish civil war in Sudan that’s caused suffering on an inconceivable scale. It snoozed through a properly evil civil war in Ethiopia that led to the kind of mass slaughter that traumatizes whole populations for good. In the 1990s and 2000s, it yawned through a conflict in the Eastern DRC that left tens of millions dead. If you’re relying on people in the rich West to care enough about the suffering of the world’s most vulnerable to get up off their asses and do something, well, you’re not making a very smart bet.

The people for whom climate is a crisis have no power.

They had basically no part in causing it. And they’re set to bear the brunt of the disaster.

It’s been 250 years since Adam Smith explained, in his Theory of Moral Sentiment, why our empathy, like gravity, is proportional to the square of the distance between us and the sufferer. We massively discount the suffering of the far away. As he put it, if you heard that, tomorrow, an earthquake on the other side of the world was going to kill a million people you’ve never met, you might feel sad about it. But you’d probably still get a nice night’s sleep. If you learned that, tomorrow, some lunatic was going to turn up and cut off your left pinky, you’d sleep a lot less well.

This happens not just in space, but also in time. We like to say we’re thinking about the consequences of our actions to the 7th generation, but realistically we’re never going to meet our great-great-great-great-great-grandchildren. They are as distant to us in time as the Sudanese are in space. Which is a shame, because climate is a crisis for them in a way it just isn’t for us. The three-degrees hotter world we’re bequeathing them is not just inconvenient — it’s murderous in ways we can only vaguely discern now. But they’re the Africans of our family tree — they feel like abstractions, not like real people.

My sense is that, in their heart-of-hearts, climate alarmist types understand all this.

They —well, the smarter ones among them, anyway— must realize that climate change isn’t really a crisis right here right now, the way it is way over there, or way over then. It’s just that the tactical lesson they draw from this insight drives them down a blind alley: trying to pretend that climate change is as threatening to us now as it is to people far away, in space or time.

That’s not true. The effort to make it feel true forces climate activists to lie a lot. People intuit the dishonesty, and it leaves them thinking this whole climate change nonsense must be a Chinese hoax.

But we should derive a different lesson from it. We could accept that yes voters are short-sighted —always have been, always will be— and they won’t support very costly policies now in return for uncertain benefits in the far distance, or in the far future. This is normal. This is unalterable. Those are the constraints we face. If you don’t accept this, you’ve given up on democracy.

I won’t give up on democracy. So I have to accept the constraints we face.

Multi-trillion dollar solutions to the climate crisis are a fantasy. Solutions that presuppose massive lifestyle changes or voluntary immiseration are not solutions at all. If you’re actually worried about the world’s most vulnerable people, you have to favor climate solutions that are compatible with political institutions as they are, not as we wish they were.

Which is all a long, roundabout way of saying we need very cheap Carbon Dioxide Removal solutions that scale. If we can find a way to take greenhouse gases out of the atmosphere at scale, we can protect the most vulnerable people, far though they are from us in space and time. In a world where the most powerful people don’t feel all that threatened by climate change, this can only be done if it can be done at very low cost. Not for thousands of dollars per ton, or hundreds, but tens of dollars, or less.

As far as I know, marine photosynthesis —via seaweed or photosynthetic plankton— is the only pathway to cheap, scalable CDR technology on offer.

So…shouldn’t we be focusing on that?

Great article, Quico! Would a tl;dr version such as the following help propagate this even further?

If you live in a poor country on the edge of agro-ecological viability, you are now experiencing a climate crisis.

If you’re a well-off person living in a rich country, you may be anxious about climate change. But you are NOT experiencing climate crisis.

Yet climate activists want your support.

They know it’s hard for you to truly care about people far away and not yet born.

So, they try to make climate change feel like an imminent crisis for you. (such as linking every domestic weather disaster to climate change)

It doesn’t work.

You probably tune out the catastrophist agenda because it feels—and is—dishonest. It might even turn you against the climate movement.

What might work?

1. An honest portrayal of the climate crisis and the people actually impacted

2. Practical, cheap, scalable solutions, such as carbon dioxide removal (CDR)

Marine photosynthesis —via seaweed or photosynthetic plankton— is the only pathway to cheap, scalable CDR technology on offer.

Wouldn’t you want to hear more about that?

I think Pope Francis’ environmental encyclical, “Laudato Si. Care for our common home,” got it right. If we think of our fellow human beings as our brothers and sisters, then empathy and compassion follow. Perhaps Pope Leo will be able to build on Francis’ efforts to bring together climate and what I think would be called prophetic religion (as opposed to sectarianism).